This telegram was sent by the Zhejiang Provincial Government to Su Benshan, the mayor of Dinghai and Xiangshan counties. Preceding the main text were two lines that clearly explained its origins:

The first line gave the source, noting that at 10:00 a.m., October 25, 1942, the telegram was dispatched from Yunhe, which was then the seat of the Zhejiang Provincial Government.

The second line stated that it was delivered at 7:00 a.m., October 26 from Zhangkeng, a village that is now part of Dajiahe Town, Ninghai County.

In March 1942, Xiangshan fell to the enemy, prompting the relocation of the Kuomintang’s party, government, and military offices to western Xiangshan and nearby villages in Ninghai, where they operated in a dispersed manner. The county mayor’s residence then moved to Guanshan Village (now part of Xizhou Town, Xiangshan), while Ding Xiang Security Corps’ radio station was set up in Zhangkeng, about 18 kilometers away.

The telegram also mentioned two dates: “Youxiao” at the beginning and “Youyang” at the end.

According to Chen En’guang, a staff of Research and Publicity Section at the Xiangshan County Archives, these were date codes, corresponding to October 17 and October 22 respectively.

Thus, it can be inferred that at noon on October 17, Su sent a telegram to the Zhejiang Provincial Government regarding the escort of three rescued British prisoners. The telegram preserved in the archives is the government’s reply to Su, likely drafted on October 22.

The dates of the telegram exchanges, the reference to “sank the enemy ship” and the name “JOHSTONE [Johnstone],” all reminded Chen of the sinking of the Lisbon Maru.

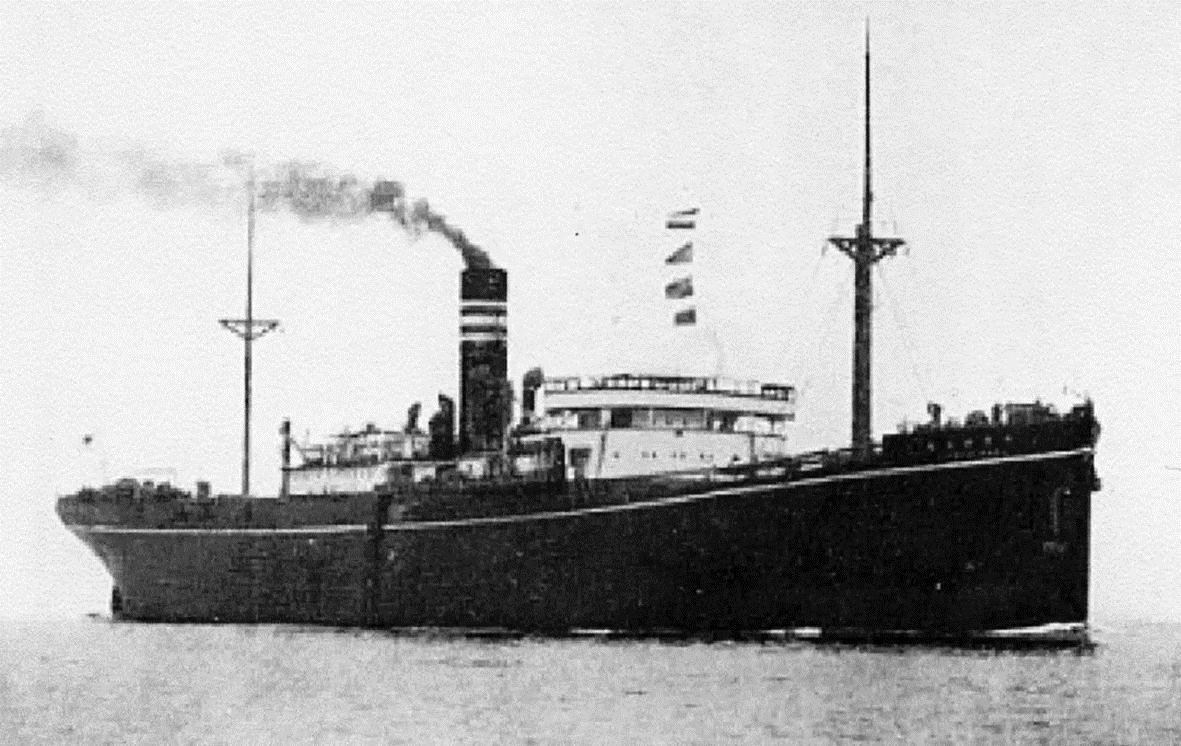

On September 27, 1942, the Japanese cargo ship Lisbon Maru departed Hong Kong, escorting more than 1,800 British POWs to Japan. On October 1, while passing through the waters near Qingbin Island in Dongji Township, Dinghai County, it was struck by a torpedo fired from an American submarine and sank in the following day.

During that time, the Japanese took no rescue measures. Instead, they nailed the holds shut with wooden planks and opened fire on British prisoners attempting to escape, killing more than 800. Another 384 were rescued by local fishermen.

On October 3, Japanese troops landed to search for survivors, capturing nearly all of the prisoners. Fortunately, three—J. C. Fallace, W. C. Johnstone, and A. J. W. Evans—escaped by hiding in a cave. They were later escorted through multiple locations to Chongqing, and eventually returned to Britain.

Was the connection between the Tianjin Maru and the Lisbon Maru merely a coincidence—or did they share a deeper link?