With the opening of treaty ports for Chinese-Western trade, Ningbo became a destination for many foreigners who traveled and settled in the city.

Many of these were female and often devoted themselves to education and healthcare. Some other females, however, were simply travelers drawn by the highly acclaimed azaleas around Xuedou Mountain―stories of their journeys have been detailed in previous chapters.

Through the eyes of women, Ningbo emerges as a city of delicacy and charm. Their observations often focus on plants, nature, and trinkets worth buying, as well as the clothing, customs, and marital traditions of Ningbo women, highlighting their roles within the family and society.

As International Women’s Day approaches, we take a closer look at Ningbo through the eyes of four remarkable women who once called it home—Helen Nevius (1833-1910), Constance Gordon-Cumming (1837-1924), Alicia Little (1845-1926), and Emily De Burgh Daly (1859-1935).

1

Ningbo Women in the Eye of Helen Nevius

Helen Nevius and her husband, John Nevius, were best known for introducing apple cultivation techniques to Yantai, Shandong Province. During their nearly 40 years in China, their efforts played a pivotal role in transforming the city into the renowned “Land of Fruit”.

The Neviuses lived in Ningbo from 1854 to 1859. Mrs. Nevius was an exceptionally talented woman who, beyond managing household duties such as cooking, needlework, and caring for her husband, was also a voracious reader and prolific writer. She authored Our Life in China (1869) and Life of John Livingston Nevius, published two years after her husband’s death in 1895.

Several passages from Our Life in China are frequently quoted, such as Helen Nevius’s account of teaching music to children in Ningbo and her observations of a Ningbo-style wedding. A significant portion of her writing also focused on the lives of Ningbo women—

“Both sexes wear loose flowing trousers, and a long double-breasted tunic or sacque, buttoned closely round the neck and at one side. The women generally wear gayer colors, and garments profusely ornamented with embroidery. At Ningpo they have a prettily made petticoat reaching nearly to their little feet, which they take special pains not to cover.”

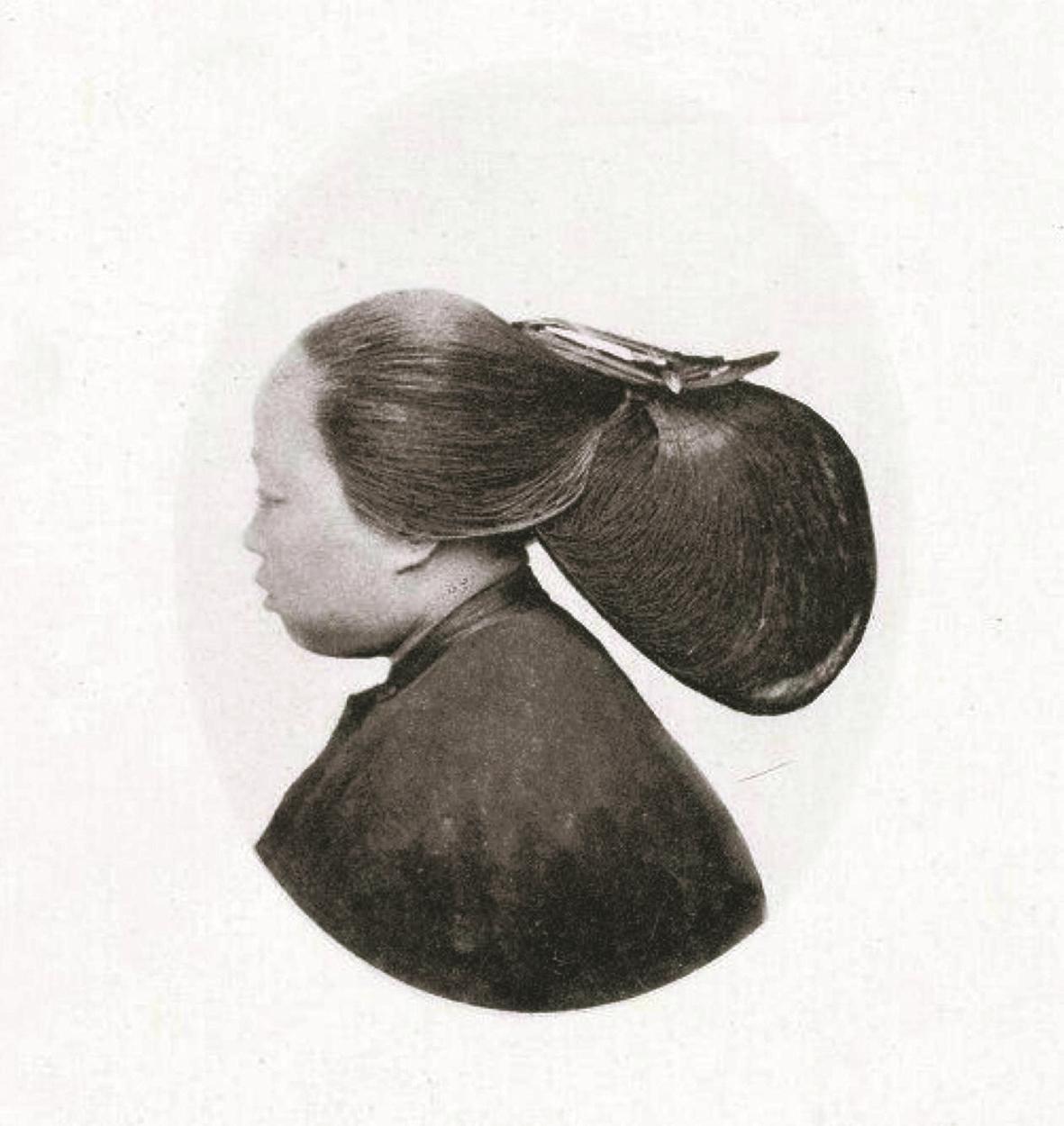

“On the whole, I think a Ningpo lady’s dress is prettier and more becoming than any of the northern costumes, or of the more southern, as far as I am familiar with them. The Ningpo style of dressing the hair, though unnecessarily artificial and elaborate, is really becoming, and more tasteful than the stiffer coiffures of ladies elsewhere. The time consumed by women in China, in arranging their hair, is much greater than is required by foreign ladies ordinarily. I have been told by our female servants that they usually spend a full hour upon theirs; while it is not unusual for persons of leisure to devote two hours to this object. But this waste of time, as it seems to us, is, I suppose, one of their most agreeable recreations, and helps to while away many an otherwise tedious hour.”

2

Encountering Ningbo’s Intangible Cultural Heritage

The British traveler Miss Constance Gordon-Cumming is no stranger to this column. Her vivid depictions of the azaleas on Xuedou Mountain were enough to “tempt” Mrs. Archibald Little to China in her footsteps.

Cumming arrived in Ningbo in May 1879 and stayed for nearly a month. In her 1886 book Wanderings in China, she described the streets and alleys of Ningbo as follows: “From every house hang pretty Chinese lanterns, and all manner of realistic signs hang from the open shops, or else tall, very narrow sign-boards, from fifteen to eighteen feet high, all carved and gilded, and gorgeously coloured, rest on carved stands beside the entrance; and as few shops have a frontage of more than ten feet.”

Among the street-hawkers, Cumming noticed “some selling very pretty artificial flowers made of fluffy silk, others selling paper umbrellas; some had ornaments of imitation jade, which might deceive even a fairly practised eye ... Among the remarkable figures are the shoe merchants, whose stock of shoes of all sizes is slung from the ends of a bamboo ... Others in the same way carry great stands of pipes, and others flowers, cakes, sugar-plums, or fish ...”

Hurrying along, she further noted “quaint bits of carving, odd stone beasts, fanciful bridges, men busy tailoring and coopering, ivory-carving, watchmaking, and fan-making, shops full of brazen vessels...where strange treasures tempt one in a way that the identical object seen in England could never do. The simplest shopping expedition (to me so wearisome in other lands) here becomes a delight.”

Unknowingly, she came across various items of Ningbo’s intangible cultural heritage —

“And then there is such never-failing interest in a show-room which is also the workshop wherein each skilful workman deftly manufactures his wares...then we come to another group whose swift needles are tracing gorgeous dragons and mythical birds on a groundwork of rich silk.” This description is reminiscent of the intricate gold and silver embroidery of dragon and phoenix motifs.

She also mentioned: “We halted for some time in a street wholly devoted to the sale of carved-wood furniture... I had full leisure to explore the innermost recesses of the shop, and examine the beautiful carvings, especially some curious large bedsteads, which answer all the purposes of a dressing-room, having drawers beneath the bed, and on either hand all necessary arrangements for washing, elaborate hair-dressing, and the application of cosmétiques, so arranged as to be shut in by an outer enclosure of beautifully carved screen-work, These, when in use, are further adorned with rich hangings of coloured silk and embroidery.” It is a clear nod to the Qiangong bed (a bed of exquisite craftsmanship that takes about 1,000 hours to complete).

Like Helen, Cumming also took note of the distinctive hairstyles of Ningbo women. “It is certainly very peculiar, and, so far as I can learn, curiously unlike that of any other district in China. A woman having rolled up her own hair quite simply, purchases two enormous wings of black hair made up on wire, and these she attaches to the back of her head, whence they project fully fifteen inches! She also purchases a small neat fold of hair with which she conceals the fastening. There is no attempt at deception in the wearing of this false hair; it is simply a head-dress, which could not possibly be made of growing hair.”