British Missionary William Charles Milne (1815-1863) arrived in Ningbo on December 7, 1842. Although his stay in the city was brief, lasting less than two months until January 30, 1843, it coincided with China’s most vibrant and widely celebrated festival—the Spring Festival.

As elaborated in the previous article, Milne spent the Chinese New Year’s Eve with a local family and received several “unexpected guests” during the first few days of the Chinese New Year. Among the visitors were officers, merchants, and craftsmen. Following local customs, Milne returned some of these visits on the third day of the festival, recognizing this ceremonial exchange as a gesture of friendship.

The festive gifts Milne received from the city officials chiefly included packets of tea, fruit, and sweetmeats, all carefully arranged in even numbers. As shown in Life in China (1857), he clarified: “... from the prevalent superstition among the Chinese, that in an odd number there is bad luck, in a complete number good. That rule is almost universal on festive occasions, especially at the opening of the new year. On the other hand, in making presents at a time of mourning for a deceased friend, or at the anniversary of his death, which it is not unusual for them to keep, the odd number prevails.”

The first day of the 1843 Chinese New Year (January 30) is very close in date to the first day of the 2025 Chinese New Year (January 29), and many of the experiences Milne had during his time continue to resonate with modern-day celebrations.

Take for example Lichun, the beginning of spring in the lunar calendar which fell on February 4. Milne mentioned that on the morning of February 3, officials―despite being on holiday―rose early to participate in a ceremony to welcome the spring.

1

“Whipping up the Spring”

Milne wrote in his diary on February 3, 1843——

“As tomorrow brings the lih-chun term, or the commencement of spring, the ceremony of introducing or meeting it (ying chun,) was conducted to-day. All the municipal officers leave their respective residences at an early hour, and go forth at the east gate. The spring comes in, it is said, at the east, summer at the south, autumn from the west, and winter from the north.”

The procession proceeded to the suburbs across the river, where there was a large building with an extensive area of open ground.

“The crowds that thronged to see the show were immense.” Milne revealed that the principal actor was the chifú: “This was the first time he had appeared in public, and it was to great advantage.” As he further described, in one spot, there was the god of the spring, or máng shin, who was worshiped. Nearby stood a brightly colored paper figure of an ox, which was also venerated. Both were ceremonially welcomed into the district. After a series of somewhat playful rituals were performed, the officials gathered to drink wine together.

“In some districts, (for exactly the same customs do not obtain everywhere,) the presiding officer on the following day strikes the senseless ox with a switch.” Milne also noted a ceremony called pien chun, meaning ‘whipping up the spring’. This ritual symbolized the beginning of springtime labor, signifying that the ox must be readied for the plough and the work of the season was to commence. “The act of whipping the poor beast is a signal for the bystanders to rush in upon it, and tear the paper frame to pieces, that man believing his ox will be a fortunate animal who can carry home a shred of the remains.”

Michael Simpson Culbertson (1819-1862), an American Presbyterian missionary who lived in Ningbo from 1845 to 1851, also observed the ceremony. He offered a more comprehensive account of this ritual in his book Darkness in the Flowery Land (1857).

“At Ningpo, a large clay figure of an ox is made, which is worshiped by the mandarins. They worship at a temple outside of the city, and when this ceremony is concluded, the Prefect ploughs a small piece of ground. The next day the officers assemble at another temple, to which the ox has been brought, and there, after offering up prayers, form a procession, and march around the ox. Each officer is provided with a bundle of twigs, with which, at signals from the master of ceremonies, he strikes the effigy. At length the Prefect strikes it on the head, and in an instant the crowd rush in and tear the ox to pieces, each anxious to procure a fragment to mingle with his seed-corn, that he may have a more abundant crop.”

2

Solar Terms

One cannot deny that Milne was a remarkably meticulous recorder.

From December 1842 to July 1843, Milne kept a diary titled Seven Months’ Residence in Ningpo, which was later published in The Chinese Repository, an English-language periodical founded by Western missionaries in China. The diary was released in seven installments, appearing in the January, February, March and July issues of 1844, as well as in the January, February, and March issues of 1847. Rich in content and detail, the diary offers valuable insights, though it has regrettably garnered little attention in modern times.

In the first issue of The Chinese Repository in 1847, Milne’s diary entry from March 6, 1843, was published. That day coincided with Jingzhe, the solar term known as the “Awakening of Insects,” and he seized the opportunity to provide an extensive introduction to China’s 24 solar terms for the Western audience. Later, when compiling Life in China, Milne integrated these insights with descriptions of Chinese New Year customs.

“Spring Signs—Lih-ts’un, or ‘beginning spring,; connected with the opening of agricultural labour for the current year; Yu-shuy, or ‘rain-water,’ the vernal showers that begin to develop and nourish universal nature; King-chih, or ‘exciting insects,’ for, according to the native entomology, this is celebrated as the time when reptiles and insects of all kinds are ‘aroused by the thunder-claps of spring out of the torpor of winter, during which they have been imbedded [embedded] in clay.’ Ts’un-fun, the vernal equinox when day and night are equally divided; Ts’ing-ming, or ‘clear brightness,’ when ‘the wind and sun are pure and genial, and the spring light is clear and cheering.’ During this term the most religious attention is paid to the sepulchres and manes of departed friends. Kuh-yu, or ‘grain rains,’ to be improved for scattering and sowing seed.”

“Summer Signs—Lih-hia, or ‘opening summer;’ Siaou-muan, or ‘little filled,’ the wheat by this time has gradually got ripe and full; Mang-chung, or ‘busy in planting,’ when the husbandman is fully occupied in transplanting the paddy; Hia-che, or ‘summer point,’ or aestival solstice, when the length of the summer day is greatest. Siaou-shoo, or ‘little heat,’ the gradual rise of warm temperature; Ta-shoo, or ‘great heat,’ during which the temperature waxes exceedingly hot.”

“Autumna Signs—Lih-ts’ew, or ‘the beginning of autumn;’ Chu-shoo, or “the extreme height of the hot temperature;’Pih-loo, or ‘white dew begins to fall;’ Ts'ew-fun, or ‘autumnal equinox;’ Han-loo, or ‘cold dew;’ the falling dew gets gradually colder; Shwang-kiang, or ‘the descent of hoar-frost.’”

“Winter Signs—Lih-tung, or ‘the opening of winter;’ Siaou-sieuh, or ‘little snow occasionally;’ Ta-sieuh, or ‘much snow,’ Tung-che, or ‘winter solstice;’ Siaou-han, or ‘the temperature falls by degrees;’ Ta-han, or ‘the temperature falls to the lowest point.’”

Milne also drew parallels between the solar terms and the zodiac signs, dedicating one of the earliest systematic introductions of China’s 24 solar terms to the Western world.

3

Chinese Almanac

When Life in China was published in 1857, Milne made significant revisions to much of the content, and the “Ningpo Chapter” appeared more logical than the previous diary style.

He also discussed the Chinese almanac, supplementing his explanation with quotes from the section “Francis Moore in China” in the October 1854 issue of Household Words.

“It is an annual, regularly published and found in the hands of every person, and on the counter of the commonest tradesman. There are various forms and editions of it, some full, others abridged; sometimes pocket manuals, sometimes sheet almanacs. But the original, which is the largest and most complete edition, is that drawn up by the Astronomical Board of Peking, sanctioned by imperial authority, issued by government at the opening of the year, and sold at every huckster-stall at the small price of three farthings or one penny. It is a complete register of the months and days of the year according to the Chinese system, its various divisions, agricultural seasons, commercial terms, official sessions and adjournments, religious festivals, and the anniversaries of the emperors and empresses of the reigning family.”

It pronounces what days are lucky or unlucky and names transactions suitable for every day, such as when to lave their persons, shave their heads, open shops, set sail, celebrate marriage, etc.

“... February 8th, 1853, ― the Chinese New Year’s day. On the first day of the first moon ― You may present your religious offerings (such as fowls or fish); you may send up representations to heaven (thanks, prayers, vows ― by burning gilt paper, straw-made figures, or fireworks in infinite variety); you may put on full dress, fur caps, and elegant sashes; you can make up matrimonial matches, or pay calls on your friends, or get married; you may set out on a journey, get a new suit of clothes commenced, make repairs about house, &c., or lay the foundation of any building, or set up the wooden skeleton of it, or set sail, or enter on a business contract, or carry on commerce, or collect your accounts, or pound and grind, or plant and sow, or look after your flocks and herds.

On the second (February 9th) you may likewise bury your dead.

On the third -- You may bathe yourself; sweep your houses and rooms; pull a dilapidated house down or any shattered wall.

On the fourth -- You may offer sacrifices, or bathe, or shave the bea[r]d, or sweep the floor and house, or dig the ground, or bury the dead.

On the fifth -- You may not start upon a journey, nor change your quarters, nor plant nor sow ……”

4

Lantern Festival

Back to Milne’s “Spring Festival Chapter”.

After the ceremony of “meeting spring” (ying-ts’un) on February 3, it was February 11, 1843, the thirteenth day of the first lunar month, when the Lantern Festival began.

Milne described in his diary that “The Feast of Lanterns ... continued through five or six days, during which term, at eventide, every corner of the city was decorated with streamers and brightly illuminated. Spectators paraded the streets in crowds, letting off crackers, rockets, squibs, and ingenious fireworks of numberless variety. Generally this is called Shangtung, ‘the feast of elevated lanterns’.”

The gala night, which falls on the first full moon of the new year, is the Saitung, or “rival lantern” night, as it calls out public emulation in the display of festal lamps. At that night, Milne went to “Tienhowkung,” “the palace of the Celestial Queen”, namely Fuhkien temple which is outside the Ningpo walls, between the East and Ling Bridge gates. “It was the most elegantly furnished building in the city. To appreciate the taste in the ornaments and the finish of the internal structure, it must be visited.”

“On that night the entire edifice glittered with lamps, lanterns, tapers, etc. The horn and glass lanterns suspended all around, had the most curious devices and scenes delineated on them, in the richest and most vivid colours. The walls were hung with native drawings in all shades, and music (such as it was) rang through decorated arches of the lofty roof; and life was given to the whole scene by the hum and gaiety of the thronging spectators.”

5

The Chinese Character “Fu”

That concludes the full content of Milne’s report on Savoring the Spring Festival of 1843 in Ningbo.

Indeed, the unique customs of the Chinese New Year inspired many descriptions in early records kept by foreigners, such as those of John Livingston Nevius (1829 - 1893) and his wife Helen S. C. Nevius (1833 - 1910), Americans who resided in Ningbo for an extended period during the 1850s. Mrs. Nevius wrote in Our Life in China (1869) that, “The Chinese do not divide their year, as we do, into an unvarying number of months and days. It is composed of lunar months, which, in order to keep the ‘wheels of time’ running smoothly, obliges them to insert every few years an additional or intercalary month.”

In 1869, her husband, Mr. Nevius, also published China and the Chinese, in which he talked about the Chinese Spring Festival, possibly based on his experience in Ningbo and Shandong. “During the night the large paper engravings pasted on the doors, representing the “Door Gods,” or “Keepers of the Doors,” have been changed, the old paper being replaced by a bright new one. New inscriptions in large red characters are also seen over the doors, resenting some sentence of joyous or propitious import. Many families make use of the single character fuh, ‘happiness,’ presenting the great end and object after which man is longing and striving everywhere ...”

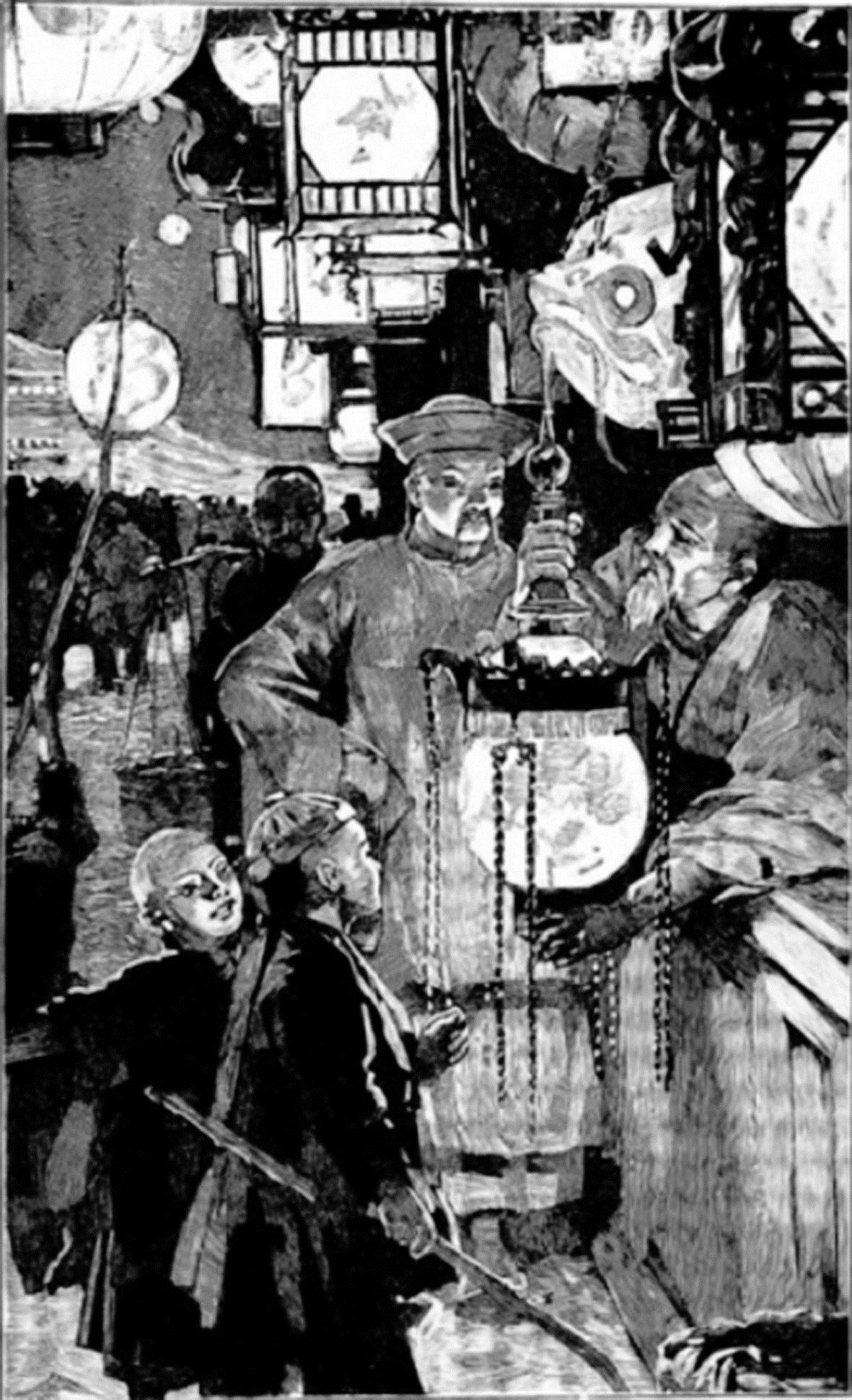

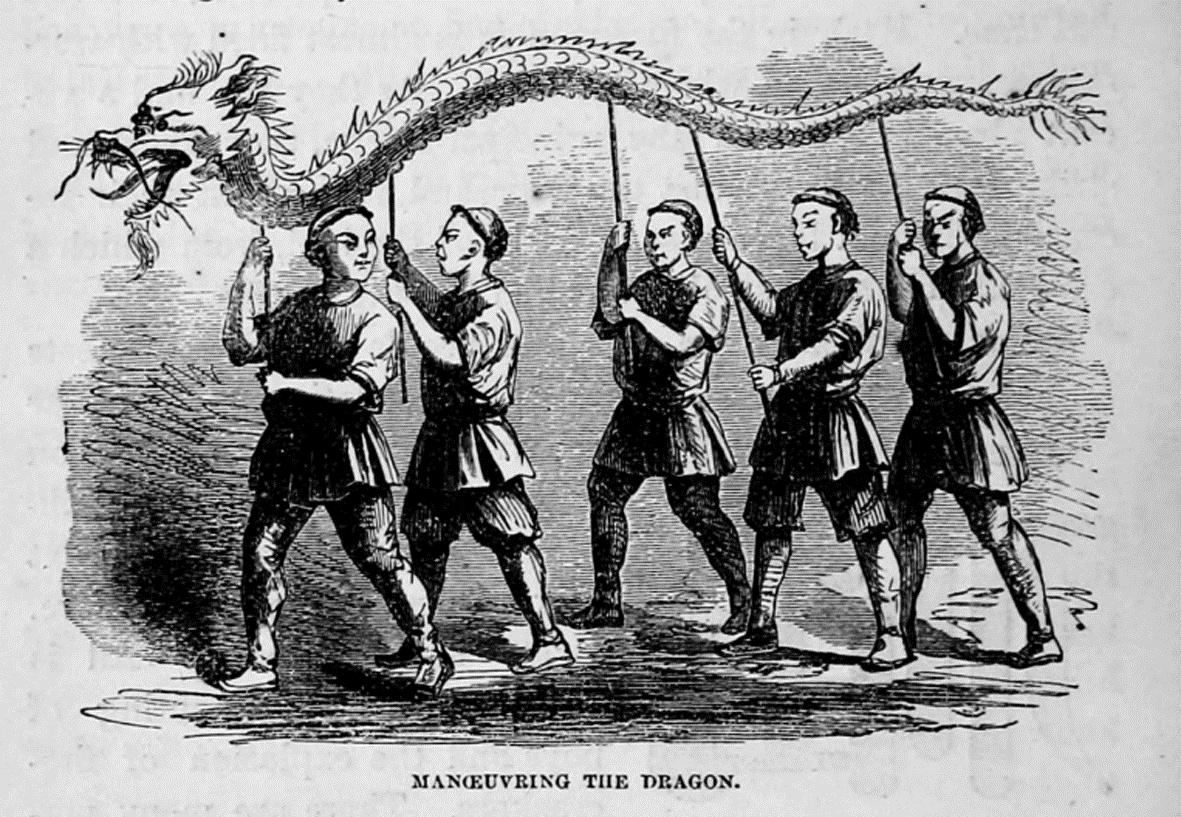

“During the festivities of the New Year it is very common to see a company of boys bearing aloft a representation of a huge dragon, made of a frame-work of split bamboo covered with cloth. With this they visit house after house, asking of the inmates the privilege of taking the dragon inside their dwelling to frighten away evil spirits, and insure good luck for the coming year. While the boys enjoy the sport greatly, they also fill their pockets with cash presented to them by the families whom they visit.”

“On the 15th of the first month occurs the ‘Feast of Lanterns.’ For several days previous, a great number and variety of lanterns are exposed for sale in the shops. They are made with a light frame of bamboo covered with transparent paper, and represent birds and animals, and other objects of interest. Some of them are made to run on wheels. Others are so contrived that the motion of the air produced by the burning of the candle sets wheels and machinery at work, and makes the object appear like a thing of life (This should be Trotting Horse Lamp ― Journalist’s note).

Due to space constraints, details presented in this article are limited. However, for those interested in learning more about Chinese New Year, additional insights can be found in Wanderings in China (1988) by the British traveler Ms. Constance Frederica Gordon-Cumming (1837-1924) and Peeps into China (1892) by the American missionary Gilbert Reid (1857-1927).

Journalist: Gu Jiayi

Translators: Pan Wenjie, Wang Siyu

Proofreaders: Yan Yujie, Fan Naxi, Jason Mowbray