Early Sketches of Xuedou Mountain

and Xikou Town

The 1860 publication of Laurence Oliphant features three sketches of Xuedou Mountain and Xikou Town, one of which shares similarities with the illustrations in Our Life in China by Helen. This sketch of “Tseen-Chang-Yen Waterfall” (Qianzhang Cliff Waterfall) has what appears to be the artist’s handwritten signature in the lower right corner, though it is somewhat difficult to make out.

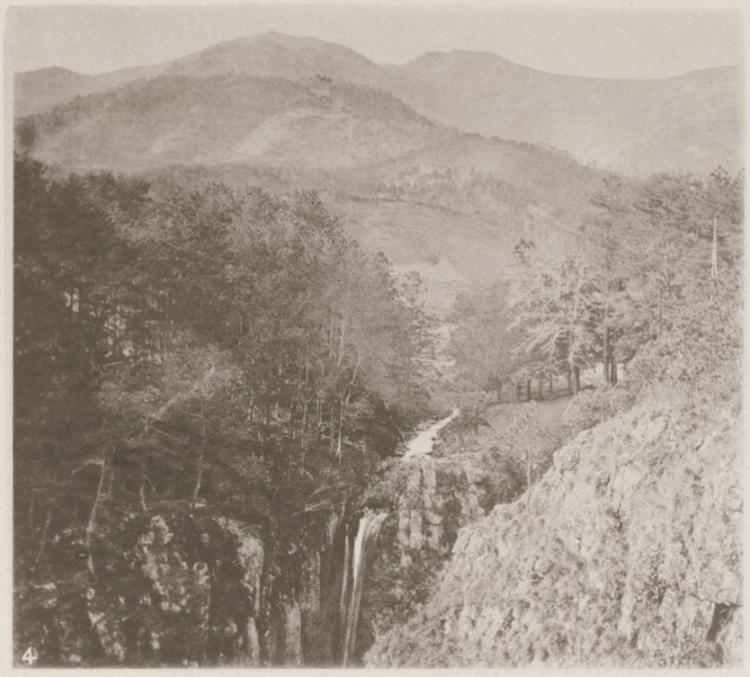

Drawn by its reputation, Laurence arrived at Xuedou Mountain sometime between 1857 and 1859. “When we had attained an elevation of about 1000 feet, and looked back from a projecting spur in the range, a beautiful panoramic view met the eye. The valley we had traversed in the morning, dotted with scattered villages, and divided by the river winding away to the horizon like a silver thread, lay at our feet, while on our right pendulous woods of bamboo covered the steep slopes of the mountain: planted with perfect regularity, their feathery plumes, of varied hues and exquisite grace of form, waved gently in the breeze.”

As he noted, the temple housed a row of Buddhist statues, the largest of which, in the center, was about twenty-five feet in height. “Huge black images, with ferocious countenances and drawn swords, guarded the sanctity of the temple; and near them was a handsome bell, where the officiating priest kept up a low monotonous chant, and tapped a little bell as the signal for genuflexion or prostration on the part of the congregation, who were in the meantime burning little pieces of yellow paper, lighting joss-sticks, or telling their rosaries.”

On the second day, Laurence toured the surrounding area, gazing over the vast, fertile valley where rivers weaved through fields. He noticed terraced rice paddies and other crops on the slopes, as well as people working in the fields or strolling along winding paths. “The scenery altogether reminded me of the Mahabuleshwar Hills, where, however, the precipices are higher.”

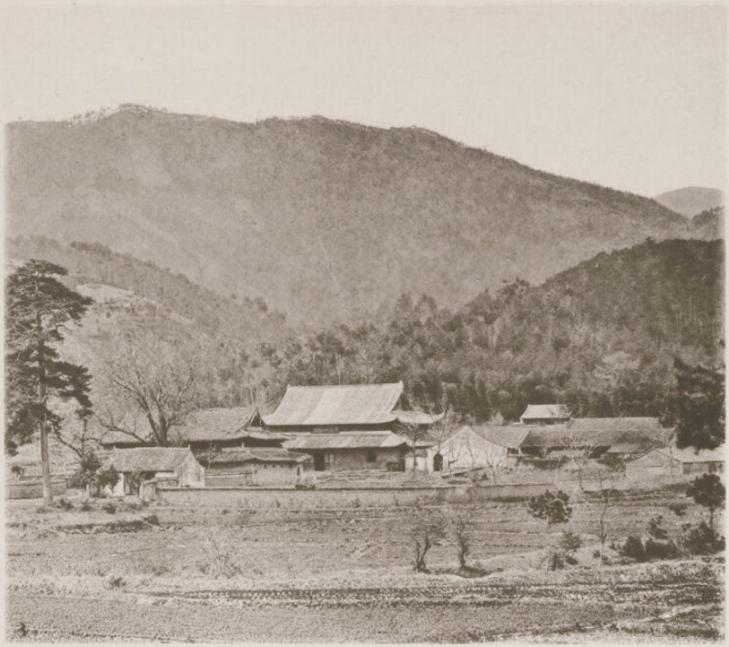

At the peak of the Qianzhang Cliff Waterfall, he gripped a pine tree and craned over to glimpse the pool beneath. The roaring waters and dizzying height made his head spin. As he descended to the foot of the fall, he was soaked by the misty spray.

By nightfall, Laurence was captivated by the stunning views near Xuedou Temple, painting the magnificent scene with vivid descriptions: “... the last faint tints of daylight were fading away on the distant mountains; the only sound which broke the absolute stillness of the repose in which all nature was hushed was the continuous plash of the water, as it issued from the deep shadows of a dense mass of overhanging foliage at the head of the gorge, in a long white sheet of foam, like a ghost in the gloaming.”

In the concluding part of this chapter, Laurence wrote: “In any country they would be worthy of a visit, but in China especially, where the limited excursions of foreigners have disclosed so little of the picturesque”; he further suggested, “no traveler should visit Ningpo without taking a trip to the mountains.”

Xuedou Mountain Through the Lens

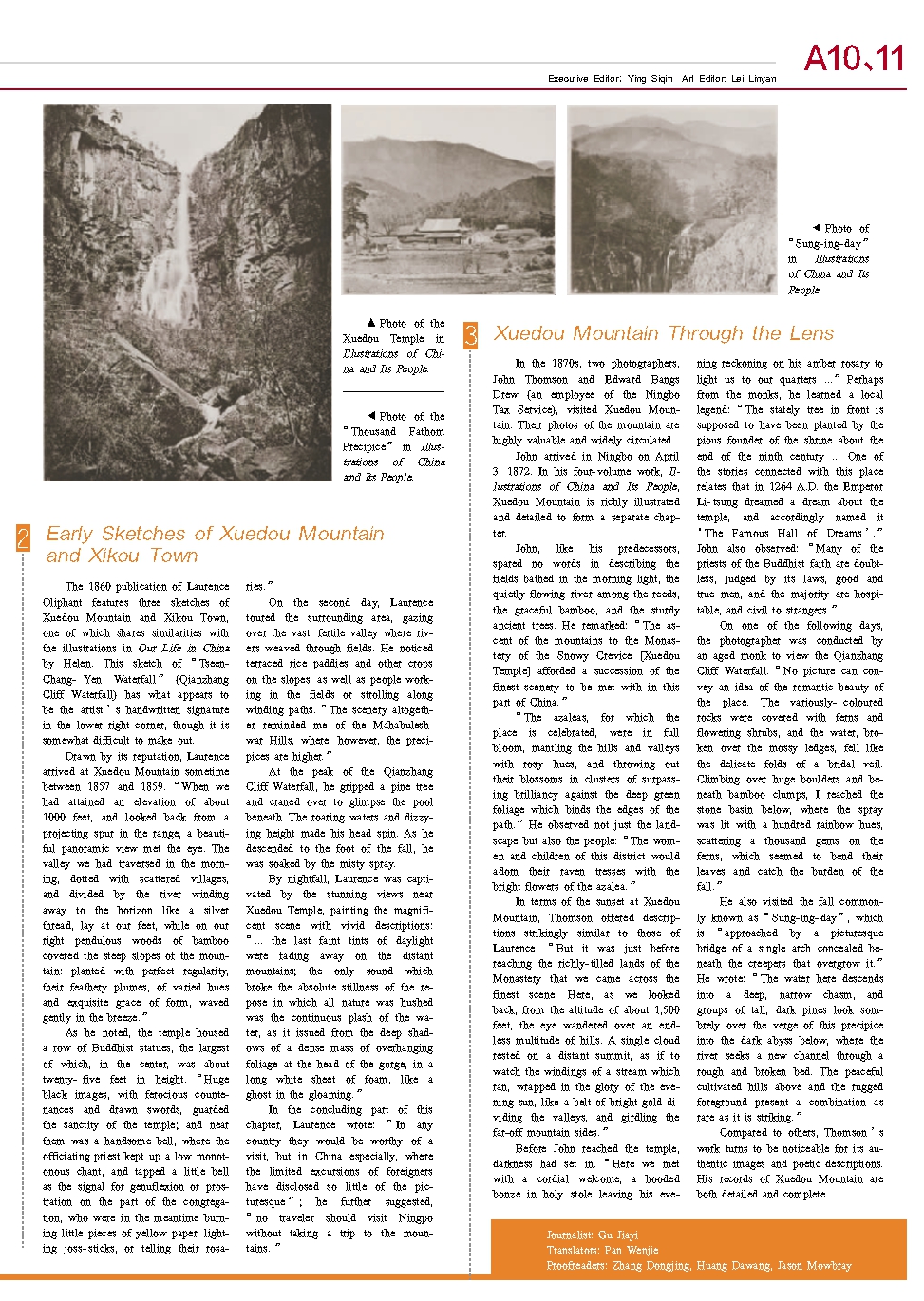

In the 1870s, two photographers, John Thomson and Edward Bangs Drew (an employee of the Ningbo Tax Service), visited Xuedou Mountain. Their photos of the mountain are highly valuable and widely circulated.

John arrived in Ningbo on April 3, 1872. In his four-volume work, Illustrations of China and Its People, Xuedou Mountain is richly illustrated and detailed to form a separate chapter.

John, like his predecessors, spared no words in describing the fields bathed in the morning light, the quietly flowing river among the reeds, the graceful bamboo, and the sturdy ancient trees. He remarked: “The ascent of the mountains to the Monastery of the Snowy Crevice [Xuedou Temple] afforded a succession of the finest scenery to be met with in this part of China.”

“The azaleas, for which the place is celebrated, were in full bloom, mantling the hills and valleys with rosy hues, and throwing out their blossoms in clusters of surpassing brilliancy against the deep green foliage which binds the edges of the path.” He observed not just the landscape but also the people: “The women and children of this district would adorn their raven tresses with the bright flowers of the azalea.”

In terms of the sunset at Xuedou Mountain, Thomson offered descriptions strikingly similar to those of Laurence: “But it was just before reaching the richly-tilled lands of the Monastery that we came across the finest scene. Here, as we looked back, from the altitude of about 1,500 feet, the eye wandered over an endless multitude of hills. A single cloud rested on a distant summit, as if to watch the windings of a stream which ran, wrapped in the glory of the evening sun, like a belt of bright gold dividing the valleys, and girdling the far-off mountain sides.”

Before John reached the temple, darkness had set in. “Here we met with a cordial welcome, a hooded bonze in holy stole leaving his evening reckoning on his amber rosary to light us to our quarters ...” Perhaps from the monks, he learned a local legend: “The stately tree in front is supposed to have been planted by the pious founder of the shrine about the end of the ninth century ... One of the stories connected with this place relates that in 1264 A.D. the Emperor Li-tsung dreamed a dream about the temple, and accordingly named it ‘The Famous Hall of Dreams’.” John also observed: “Many of the priests of the Buddhist faith are doubtless, judged by its laws, good and true men, and the majority are hospitable, and civil to strangers.”

On one of the following days, the photographer was conducted by an aged monk to view the Qianzhang Cliff Waterfall. “No picture can convey an idea of the romantic beauty of the place. The variously-coloured rocks were covered with ferns and flowering shrubs, and the water, broken over the mossy ledges, fell like the delicate folds of a bridal veil. Climbing over huge boulders and beneath bamboo clumps, I reached the stone basin below, where the spray was lit with a hundred rainbow hues, scattering a thousand gems on the ferns, which seemed to bend their leaves and catch the burden of the fall.”

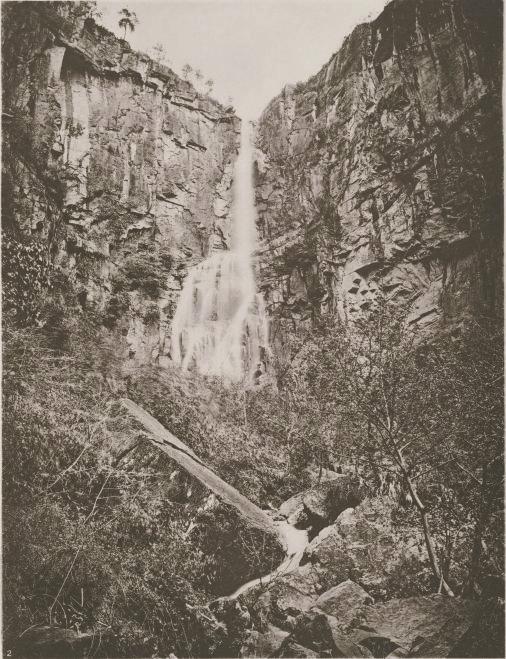

He also visited the fall commonly known as “Sung-ing-day”, which is “approached by a picturesque bridge of a single arch concealed beneath the creepers that overgrow it.” He wrote: “The water here descends into a deep, narrow chasm, and groups of tall, dark pines look sombrely over the verge of this precipice into the dark abyss below, where the river seeks a new channel through a rough and broken bed. The peaceful cultivated hills above and the rugged foreground present a combination as rare as it is striking.”

Compared to others, Thomson’s work turns to be noticeable for its authentic images and poetic descriptions. His records of Xuedou Mountain are both detailed and complete.

Journalist: Gu Jiayi

Translators: Pan Wenjie

Proofreaders: Zhang Dongjing, Huang Dawang, Jason Mowbray