A Reasonable Misreading of

the Appellation ‘Tianfeng’

In 1843, shortly after Milne left Ningbo, the British botanist Robert Fortune arrived in Ningbo that autumn.

Fortune’s mission to China was to find superior and transplantable tea varieties, earning him titles such as “plant hunter” and “Prometheus of tea.”

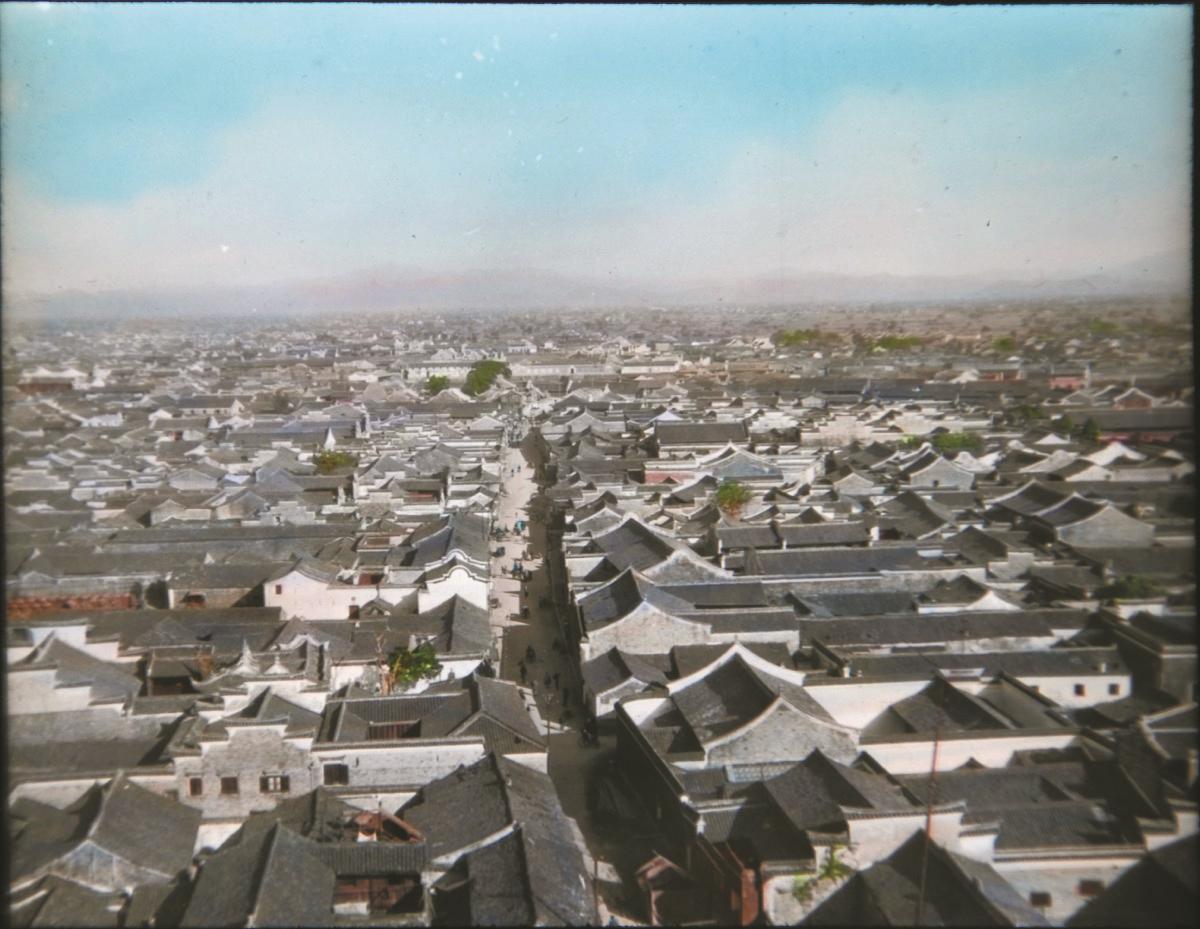

To Fortune, Ningbo appeared to be a large, well-fortified city with high walls and ramparts extending about five miles. He noted, “The city itself is strongly fortified with high walls and ramparts about five miles round”. “A good view of the city and the surrounding country, as far as the eye can reach, is obtained from the top of a pagoda about one hundred and thirty feet high, having a staircase inside by which the top can be reached. This pagoda is named ‘Tien-foong-tah’.”

The original characters “封 (bestowment)” and “风 (wind)” are both pronounced as ‘feng’, but Fortune did not confuse this couple of heterographs or make a spelling error; rather, he genuinely believed that the pagoda’s name meant “Temple of the Heavenly Winds”, in favor of “Temple of the Heavenly Bestowment”.

In his book Two Visits to the Tea Countries of China (1853), there is a sketch of Tianfeng Pagoda, which also appears in George Cobbold’s Pictures of the Chinese (1860), suggesting that these early British visitors may have shared visual resources.

Fortune’s misinterpretation was not an isolated case. The British missionary George Smith, who arrived in Ningbo in 1845, also referred to Tianfeng Pagoda as “Tien-foong-tah” in his 1847 publication A Narrative of An Exploratory Visit to Each of the Consular Cities of China, interpreting it as “The Tower of Celestial Wind.”

Smith visited the pagoda on the evening of July 23, 1845, and wrote a remarkably vivid description: “And as he gradually ascends, the view from the windows of each story is increasingly grand and magnificent. Beneath his feet lie the living masses of a populous city, teeming with busy toil. Every variety of form, size, and colour helps to heighten the novel effect, and imparts a feeling of romance to the objects before him. The numerous temples reared by native superstition, the curiously-devised buildings, the grotesque style of architecture, the elaborately-formed roofs, the strangely-sculptured arches, the various emblems of civic authority, and the irregular range of public buildings, form one successive group of motley objects, as far as the eye extends.”

“On three sides the city is surrounded by streams .... To the east lies the river, with an assemblage of native junks on its waters. Beyond the walls an extended plain stretches forward amid a fertile and productive county, till, at the distance of ten or twenty miles, the bold line of hills, rising in the sky, gives a completeness to the scene.”

He wrote with deep emotion: “Here, if anywhere, will the traveller, as he views the moving panorama of life, realize the feeling, that he is in a new world of men and things.”

A poem about Tianfeng Pagoda by Yuan dynasty (1206-1368) poet Dong Xun (whose birth and death dates are unknown) resonates similarly with Smith’s sentiments: “Step by step, I ascend the precarious tower, reaching towards the heavens. // Encircled by a thousand leagues of cityscape, clusters press upon spring mountains. // Birds perch steadily on the rail, clouds leisurely gather below. // After ten years, standing at this vantage, I finally smile at the view.”

Rekindling the Night View of

Tianfeng Pagoda

Like William C. Milne, George Smith also noticed the dilapidation of Tianfeng Pagoda: “It has suffered a larger than average proportion of disasters from casualties and the ravages of the elements. Its exterior bears the mark of age in the half-tottering appearance of the whole edifice.”

“The interior is in a better state of preservation, having been repaired, about six years ago, by a Chinese gentleman, of some local celebrity, named Wang, who is said to have expended 3000 dollars on the building. His public spirit and liberality have been emulated by another wealthy Chinese, named Fung, who has amassed an immense fortune by his junks trading in the Eastern Ocean, and now resides at a little distance from the city, at a place called Tze-ke. There he seeks to enjoy the comforts and splendour of wealth, and the more substantial luxury of doing pairing temples, beautifying public buildings, and mending the roads in the vicinity.”

Tianfeng Pagoda’s restoration around 1840 is not documented in Chinese historical sources, instead, George Smith’s account provides additional insight into this period.

In addition to English recordings, a French official working for the Ministry of Foreign Trade, Auguste Haussmann, also left his mark on the Tianfeng Pagoda. He traveled to China between 1843 and 1844, and published his three-volume book Travels in China, India, and Malaysia (Voyages en Chine, Cochinchine, Inde et Malaisie) in 1847-1848 after he returned home. In a chapter called Field Trip to the Chinese Export Trade, he mentions the Tianfeng Pagoda -

“Ningbo boasts a large number of historical monuments. Perhaps the most striking of these is a seven-story pagoda .... The pagoda is in the shape of a hexagon and is about 50 meters high. Each floor of the pagoda has six windows. The walls of the entire building have been severely damaged, with deep cracks seen everywhere, from which tufts of grass emerge, making it a complete wreck.”

“There used to be a corridor covered with arched roof on each floor of the pagoda, until a fire destroyed all these ornaments. An old monk who lives in a monastery located behind the pagoda is the custodian of the keys to the entire building where he brings in the foreigners for a few pennies.”

“I counted 12 stairs with a total of 147 steps. These stairs, like the floors and windows, become progressively smaller as one approaches the top of the tower, where one spots at its feet thousands of arched roofs, numerous temples, a vast plain of prosperity and fertility, and the Tahia River, which fades from view after a number of detours.”

“On the walls of the pagoda I read the names of several sailors of the French corvette called l’Alcmène, which had visited Ningpo the previous year. It is said that on festive days, the whole building is illuminated, with a lantern hanging from every window, thus creating a charming sight.”

The fire mentioned by Auguste took place on the third night of the 12th lunar month in 1798. On this dark and windy winter night, the lamplighter lit the lanterns of the Tianfeng Pagoda step by step. Unexpectedly, sparks suddenly splashed out and dropped onto the surrounding timber panels.

It can only be wondered how the people of Ningbo viewed the burning of the Tianfeng Pagoda level by level on that freezing night, and whether they felt the same sense of sadness as the French as they witnessed Paris’ Notre Dame Cathedral being consumed by flames. The Chinese local record of this incident is: “New tablets and old inscriptions, none survived”. Perhaps it was after that the Tianfeng Pagoda gradually tilted and became the “Leaning Tower of Ningbo”.

In the 1980s, the wall of Tianfeng Pagoda underwent increasingly deteriorated cracking, endangering the surrounding residents whenever the typhoon season came. Ningbo people made a painful decision to dismantle and reconstruct Tianfeng Pagoda and reopened it to the public in 1989.

As reported, Ningbo Cultural and Tourism Department is planning to ‘rekindle’ the nightscape of Tianfeng Pagoda. This show-stopping display with luminous lanterns, which once left a profound impression on William C. Milne and Auguste Haussmann, is expected to reappear.

Journalist: Gu Jiayi

Translators: Pan Wenjie, Wang Siyu (intern)

Proofreaders: Yao Zhanhong, Huang Dawang, Fan Naxi, Jason Mowbray