More than 160 years ago, which street hawkers and vendors were active in Ningbo? And how did these professionals ― dentists, sugar vendors, wine carriers, lantern sellers, as well as gardeners, stonemasons, barbers, and water carriers ― ply their trades and navigate their daily lives?

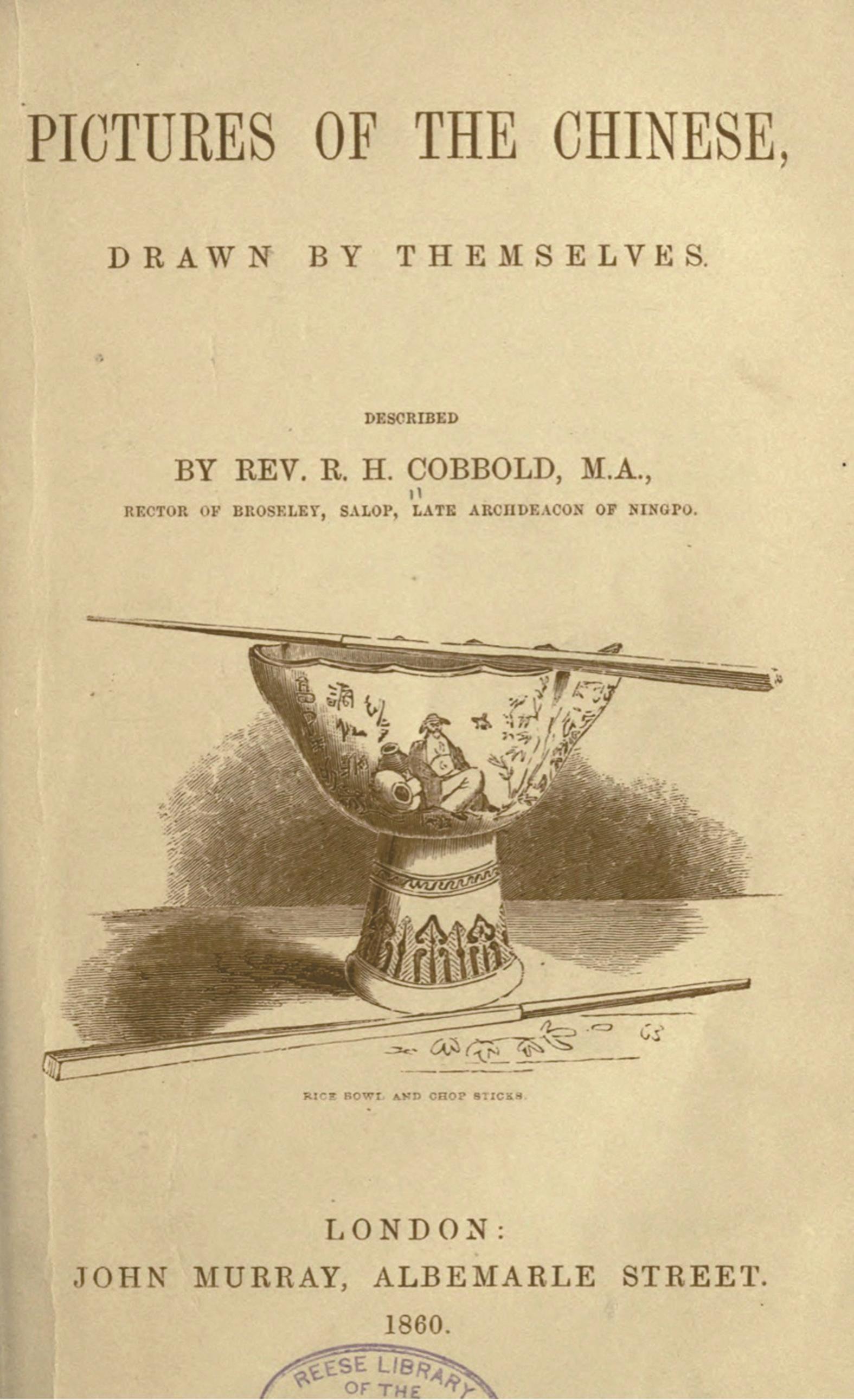

Pictures of the Chinese, Drawn by Themselves was published in London in 1860 and the book introduced the various trades and professions of the late Qing Dynasty.

The author, Robert Henry Cobbold (1820-1893), offers a portrayal of the diverse tapestry of late Qing-era eastern Zhejiang’s urban life based on his residence of eight years in Ningbo and frequent travelling throughout Zhejiang Province. The book inherits the Chinese narrative tradition of “picture on the left and texts on the right,” and before introducing each profession, there would be a sketch presented (in the form of pen-and-ink etching and contributed by a native artist of Ningbo). The blend of images and words can set off each other for a richer reading experience.

This book stands out as a rare endeavor of Western authors, presenting a visual narrative of the humanistic customs and daily life of the Chinese people. Its entertaining and vivid writing brings an earthly atmosphere.

2017 saw the translation of this book into Chinese (《市井图景里的中国人》). Xuelin Press included the work in its series of History, Geography and Customs within European and American Sinology. Notably, its translator is Liu Ben, an English teacher at Ningbo No. 3 High School.

Female Dentist and Wastepaper Basket

Cobbold, author of Pictures of the Chinese, Drawn by Themselves, was an Anglican missionary, graduating from Peterhouse College of Cambridge University.

Cobbold came to China in 1848 and arrived in Ningbo on May 13th of the same year. In September 1851, he returned to England to report on his duties and then came back to Ningbo with his newlywed wife in January 1853. They lived there until March 1857, spending a total of eight years in this Chinese coastal city, during which he also traveled to various places across Zhejiang.

Whilst in China he prepared his book, Pictures of the Chinese, Drawn by Themselves, which was published by John Murray in 1860. Each chapter of the 30-chapter book introduces a local profession, ranging from weddings and funerals, festivals and customs, food and clothing, craftsmen and artists, Taoist priests and physicians, and diviners and seers.

For example, Chapter 1 (“The Infallible Remedy”) describes in detail how female quacks in Ningbo extract toothworms or maggots for people. The verse “Granny plays a trick to coax toothworms out” comes from an old Ningbo nursery rhyme. Westerners living in Ningbo at the time were keenly interested in but skeptical of this mysterious healing remedy, so Cobbold decided to test it out and recorded the whole process in vivid and engaging prose ...

“Our engraving conveys a very truthful representation of this class of women: they are known by their long umbrellas, their small feet, and their very neat head-dress, and have the character of being well able to defend themselves if rudely attacked.” Cobbold depicts.

Another frequently cited etching is “The collector of Paper Scraps”. In ancient China, there was a tradition of revering and sparing printed paper, and the waste-paper had to be put into a separate fireplace, often erected in the side court of a temple, to be incinerated. Today, Tiantong Temple in Ningbo still retains a word-sparing furnace, on which there is a couplet “Venerate words and paper for infinite blessings, cherish literary treasures for generations to come”.

“Every scholar keeps in his study a waste-paper basket, which is accurately represented in the hand of the figure standing at the door of his house.” Describing the illustration, Cobbold says, “When the cry of the man with the large baskets, King sih sze tsze, ‘Revere and spare the printed paper’ is heard, then he will go or send his servant to the door, and empty the contents of his basket into the light and capacious skep of the collector.” The wicker basket in this illustration has “Yongjingshe” written on it, with a small flag that reads, “Guangwenhui reveres and spares the printed paper”.

Cobbold also mentions, “In the city of Ningpo [now known as Ningbo], distant only fifteen miles from the sea, I have known them put in charge of a trusty servant, floated down to the mouth of the river, and then cast into the strong ebb tide, that they might mingle with the waters of the wide ocean, and be effectually saved from all fear of profanation.” This is a special way for the scholars in Ningbo to deal with printed paper.

Roadside stalls and bazaars

Within the bustle and hustle of roadside stalls and bazaars, you can find the earthly joy of Chinese society.

Chapter 28 of Pictures of the Chinese, drawn by themselves focuses on the food stalls, presenting us with four illustrations: “selling wonton,” “selling gelidium jelly,” “selling soybean milk” and “selling tangyuan.” As written by its author, Robert Henry Cobbold, “Photography itself could hardly exceed in the accuracy of these drawings.”

“A stall, like that engraved on the opposite page, is carried on the back of the owner, and set down at some convenient corner of a street, where it remains till purchasers have exhausted its contents. … If I may give the result of occasional investigation, I should say that the chief article of food which here tempts the palate, consists of very small rice-flour dumplings, stuffed with a sweet confectionery, and stewed in sweetsauce. … By the two paper lanterns attached to the portable cook-shop, we are reminded that the owner is preparing to open his restaurant for evening customers.”

Although he found it somewhat challenging to accurately distinguish the unique snacks offered by the four stalls, his descriptions of these Chinese delicacies clearly convey his admiration — “I will venture to state my conviction that there are few countries which produce such a variety of cheap and good food as China; fewer still which will bear comparison with her people in the art of cooking. Although no mutton or beef is used at the tables of the wealthy, yet the variety of entrees is hardly exceeded by any nobleman’s table in England.”

In chapter 29, Cobbold also offers a detailed description of various fresh goods available at the Ningbo bazaar.

“The market supplies you with a great variety of good provision[s]. Here are snake-like eels wriggling and intertwining in large pans; there pails of oysters without their shells, just brought, on the backs of strong coolies, a distance of twenty miles. Here, again, are crabs of every size, from the little brown variety, which, for two months in the year, are eaten raw and alive, being merely dipped into a saucer of vinegar on their way to your mouth; or, if you prefer them, there is the large kind which have been preserved in brine, and which, like the beef-hams of America, to cook is to spoil.” “The larger kind” obviously refers to the Ningbo red cream crab.

In the market, Cobbold also encountered trepangs, frogs, soft shell turtles, cockles, periwinkles, mussels, and several other shellfish he couldn’t identify.

“All alive, or packed in ice, or preserved in salt, are fish, large and small, good and bad, adapted to the means of all customers. The cuttlefish swims in its own inky liquid, tempting the man of moderate means, who cannot afford the richer delicacies. Of poorer food still, there are the different kinds of sea-weed, brown and green; or refuse shrimps dried and salted, forming a cheap relish for the cottager's rice. All vegetable produce is there—sweet potatoes, yams, taros, turnips, carrots, beans, peas, and cabbages, melons and cucumbers, according to the season.”

These variations are not far from what we have today.