Ningbo Craftsmanship

Cobbold also made detailed observations of the craftspeople in China, including needle-makers, florists, stone-squarers, barbers, tailors, cobblers, and braziers.

In a chapter on stone-squarers, Cobbold recalled his two trips to the stone quarries in what is now Dayin Town, Yuyao County, Ningbo. He wrote: “A common object of interest to foreigners residing at Ningpo, is the scene of the stone quarries at Da-ying. They lie about fifteen miles to the north of the city, and may be reached either altogether by water, or partly by water and partly by land. The latter forms the more interesting journey.”

“At the foot of the hill, just before the rugged pathway winds into its excavated side, masses of stone meet the eye, which have been brought down thus far either on strong and effective barrows, or by means of poles on men’s shoulders. They lie ready for the merchant, for a branch of the Ningpo river runs up to this point, and affords convenience for transport.”

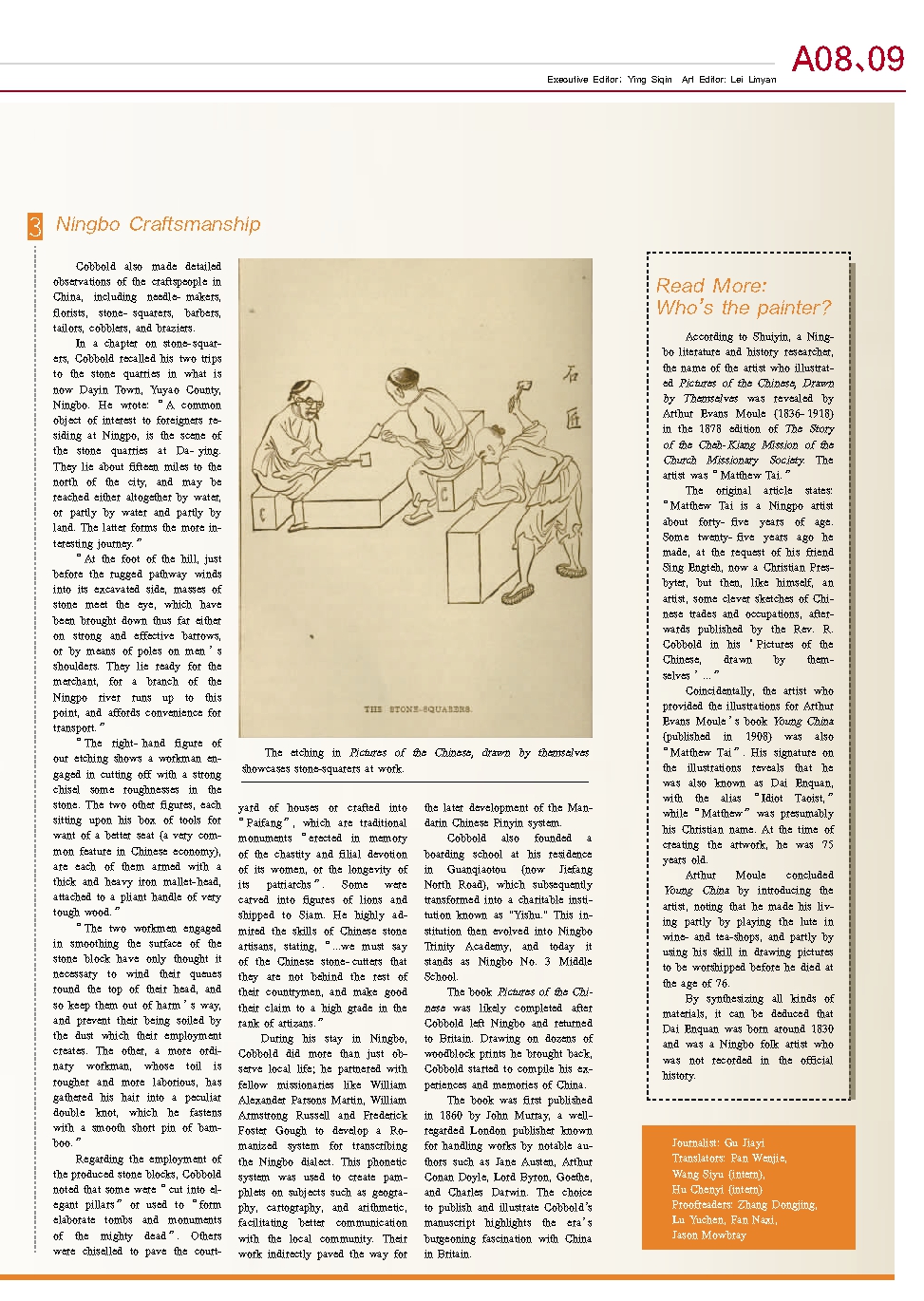

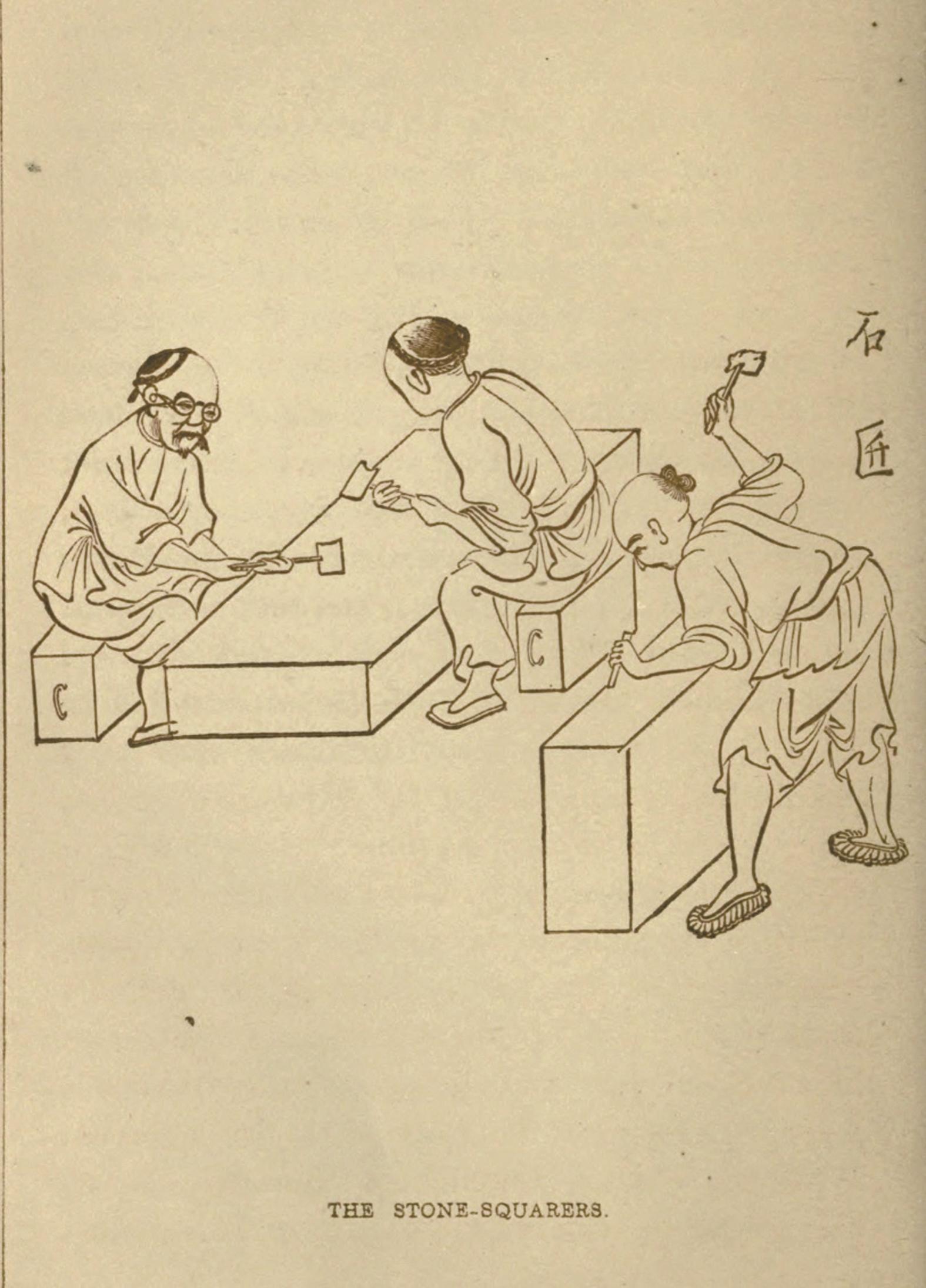

“The right-hand figure of our etching shows a workman engaged in cutting off with a strong chisel some roughnesses in the stone. The two other figures, each sitting upon his box of tools for want of a better seat (a very common feature in Chinese economy), are each of them armed with a thick and heavy iron mallet-head, attached to a pliant handle of very tough wood.”

“The two workmen engaged in smoothing the surface of the stone block have only thought it necessary to wind their queues round the top of their head, and so keep them out of harm’s way, and prevent their being soiled by the dust which their employment creates. The other, a more ordinary workman, whose toil is rougher and more laborious, has gathered his hair into a peculiar double knot, which he fastens with a smooth short pin of bamboo.”

Regarding the employment of the produced stone blocks, Cobbold noted that some were “cut into elegant pillars” or used to “form elaborate tombs and monuments of the mighty dead”. Others were chiselled to pave the courtyard of houses or crafted into “Paifang”, which are traditional monuments “erected in memory of the chastity and filial devotion of its women, or the longevity of its patriarchs”. Some were carved into figures of lions and shipped to Siam. He highly admired the skills of Chinese stone artisans, stating, “...we must say of the Chinese stone-cutters that they are not behind the rest of their countrymen, and make good their claim to a high grade in the rank of artizans.”

During his stay in Ningbo, Cobbold did more than just observe local life; he partnered with fellow missionaries like William Alexander Parsons Martin, William Armstrong Russell and Frederick Foster Gough to develop a Romanized system for transcribing the Ningbo dialect. This phonetic system was used to create pamphlets on subjects such as geography, cartography, and arithmetic, facilitating better communication with the local community. Their work indirectly paved the way for the later development of the Mandarin Chinese Pinyin system.

Cobbold also founded a boarding school at his residence in Guanqiaotou (now Jiefang North Road), which subsequently transformed into a charitable institution known as "Yishu." This institution then evolved into Ningbo Trinity Academy, and today it stands as Ningbo No. 3 Middle School.

The book Pictures of the Chinese was likely completed after Cobbold left Ningbo and returned to Britain. Drawing on dozens of woodblock prints he brought back, Cobbold started to compile his experiences and memories of China.

The book was first published in 1860 by John Murray, a well-regarded London publisher known for handling works by notable authors such as Jane Austen, Arthur Conan Doyle, Lord Byron, Goethe, and Charles Darwin. The choice to publish and illustrate Cobbold’s manuscript highlights the era’s burgeoning fascination with China in Britain.

Read More:

Who’s the painter?

According to Shuiyin, a Ningbo literature and history researcher, the name of the artist who illustrated Pictures of the Chinese, Drawn by Themselves was revealed by Arthur Evans Moule (1836-1918) in the 1878 edition of The Story of the Cheh-Kiang Mission of the Church Missionary Society. The artist was “Matthew Tai.”

The original article states: “Matthew Tai is a Ningpo artist about forty-five years of age. Some twenty-five years ago he made, at the request of his friend Sing Engteh, now a Christian Presbyter, but then, like himself, an artist, some clever sketches of Chinese trades and occupations, afterwards published by the Rev. R. Cobbold in his ‘Pictures of the Chinese, drawn by themselves’ ...”

Coincidentally, the artist who provided the illustrations for Arthur Evans Moule’s book Young China (published in 1908) was also “Matthew Tai”. His signature on the illustrations reveals that he was also known as Dai Enquan, with the alias “Idiot Taoist,” while “Matthew” was presumably his Christian name. At the time of creating the artwork, he was 75 years old.

Arthur Moule concluded Young China by introducing the artist, noting that he made his living partly by playing the lute in wine- and tea-shops, and partly by using his skill in drawing pictures to be worshipped before he died at the age of 76.

By synthesizing all kinds of materials, it can be deduced that Dai Enquan was born around 1830 and was a Ningbo folk artist who was not recorded in the official history.