“Liberty and love.

These two I must have.

For my love, I’ll sacrifice my life.

For liberty, I’ll sacrifice my love.”

On June 11, the 114th anniversary of Ningbo poet and translator Yin Fu’s birth, international guests gathered at the Garden of the Translators of Petőfi Poems in south Hungary’s Kiskunfélegyháza to witness the unveiling of a memorial statue in Yin’s honor. Famously, the Chinese translation of Sándor Petőfi’s Szabadság, szerelem! (Liberty and Love) that is best known and most recited across China was rendered by Yin. This ceremony symbolized a timeless encounter between Hungary’s most renowned poet and the Chinese translator of his poetry in China.

“If Yin Fu, also known as Bai Mang, had not translated this poem in such a unique manner, none of this would have come true, and Petőfi would not have become a pivotal figure in Sino-Hungarian cultural relations,” said Li Zhen passionately at the unveiling ceremony. Li, an expat who has been honored with the title “Knight of Hungarian Culture”, is celebrated as both a literary translator and a researcher of Petőfi.

When soulmates meet

At the Garden of the Translators of Petőfi Poems on the afternoon of June 11, anticipation filled the air as everyone awaited the moment when Sándor Petőfi would finally “meet” his Chinese “soulmate” Yin Fu.

Sándor Petőfi (1823-1849) is celebrated as a great patriotic poet of Hungary, while Yin Fu (1910-1931) is renowned as a famous revolutionary poet in China and one of the “Five Martyrs of the League of Left-Wing Writers”. Despite being born nearly a century apart, their lives shared remarkable similarities: both were poets, revolutionaries, and both sacrificed their lives for their revolutionary causes in their twenties.

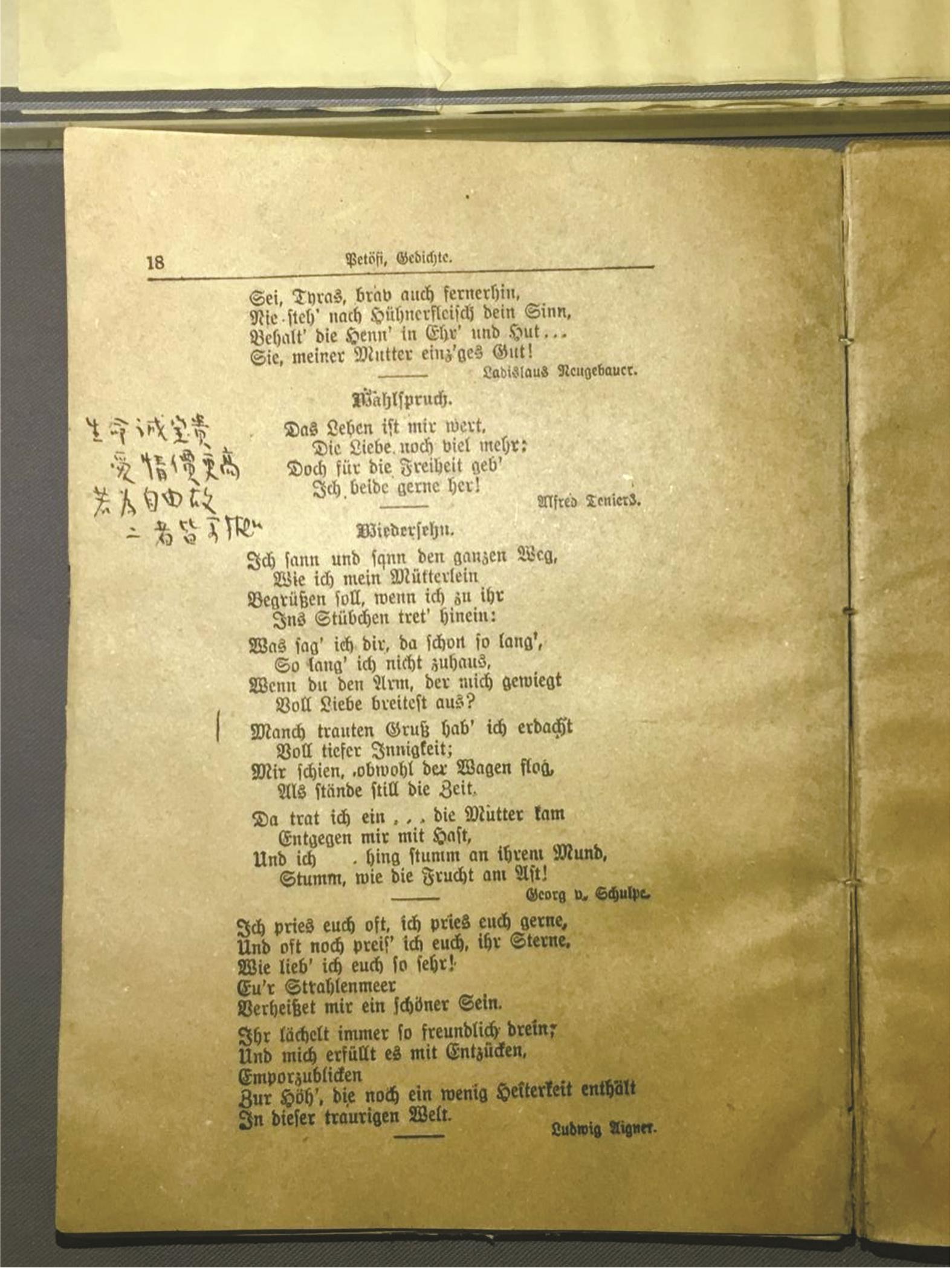

Moved by these parallels, Yin could not contain his empathetic excitement when he first read Wahlspruch (“Motto”), a German translation of Petőfi’s Szabadság, szerelem! (now known as Liberty and Love in English). Inspired, he penned the Chinese translation which became ingrained in the cultural consciousness of China.

As the crowd watched intently, Mayor József Csányi of Kiskunfélegyháza, Xing Mengjun from Ningbo Municipal Government, Liu Yu from the Chinese Embassy in Hungary and Li Zhen unveiled the memorial statue of Yin. The Jura beige limestone monument contains a relief sculpture of Yin and an engraved biography. Since Yin conducted research and translation of Petőfi’s works under the pen name Bai Mang, it is the latter name that is inscribed on the monument.

The garden already features four monuments honoring the translators of Petőfi’s works into Romanian, German, English, and Italian. The Yin Fu monument is the fifth permanent memorial.

At the unveiling ceremony, József Tarjányi, Hungarian researcher of Petőfi and member of the National Sándor Petőfi Society, shared a heartfelt story of his encounter with Petőfi’s poem in China. “In 2016, during a trip to China, I asked our guide if she had heard of Petőfi. She nodded and asked for a piece of paper... She then turned around and wrote the entire poem Liberty and Love on a napkin,” he recalled. “This piece of napkin is now one of my most cherished Petőfi-related treasures.”

Li attended the unveiling ceremony and expressed great admiration for Yin’s translation of Liberty and Love.

As Li explained, poetry translation is particularly challenging, as subtleties can easily be lost in translation. Retaining the original linguistic elements such as rhymes requires even more effort and talent on the part of the translator. Petőfi’s original work, written in Hungarian, is a six-line metrical poem. But Yin’s translation was based on the German translation by Alfred Teniers, which rendered it as a four-line poem with rhymes on the second and fourth lines. Yin managed to retain these rhymes beautifully. The rhyme between ‘gao’ (‘high’) in the second line and ‘pao’ (‘discard’) in the fourth is particularly memorable.

“I personally believe there is no better translation than this.” Li added that Yin’s translation resonates deeply with Chinese readers’ aesthetic tastes. Many people, upon reading the poem, even believe it to be a native Chinese creation.