In 1937, the American James Marshall Plumer brought global renown to Ningbo’s Shanglin Lake Yue Kiln Site with three articles. Today in 2024, Ningbo’s Cixi County extends an invitation to Plumer’s descendants.

On June 2, the Research Achievements Symposium on the International Dissemination History of the Culture of Yue Kiln Mi-se Porcelain from Shanglin Lake in Modern Times was held at the Shanglin Lake Celadon Cultural Heritage Park, Cixi County, Ningbo.

The Celadon Culture Heritage Park, adjacent to Shanglin Lake, was chosen as the meeting venue for its special significance. Cixi County, located in the northern part of Ningbo, Zhejiang Province, is renowned as “the capital of Mi-se Porcelain” in China. The Yue Kilns here represents the longest-lasting cluster of kilns in China, spanning over a thousand years from the Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220 AD) to the Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279 AD). Shanglin Lake, home to most of the Yue Kilns, is celebrated as the world’s largest open-air celadon museum and the sole origin of the imperial Mi-se Porcelain.

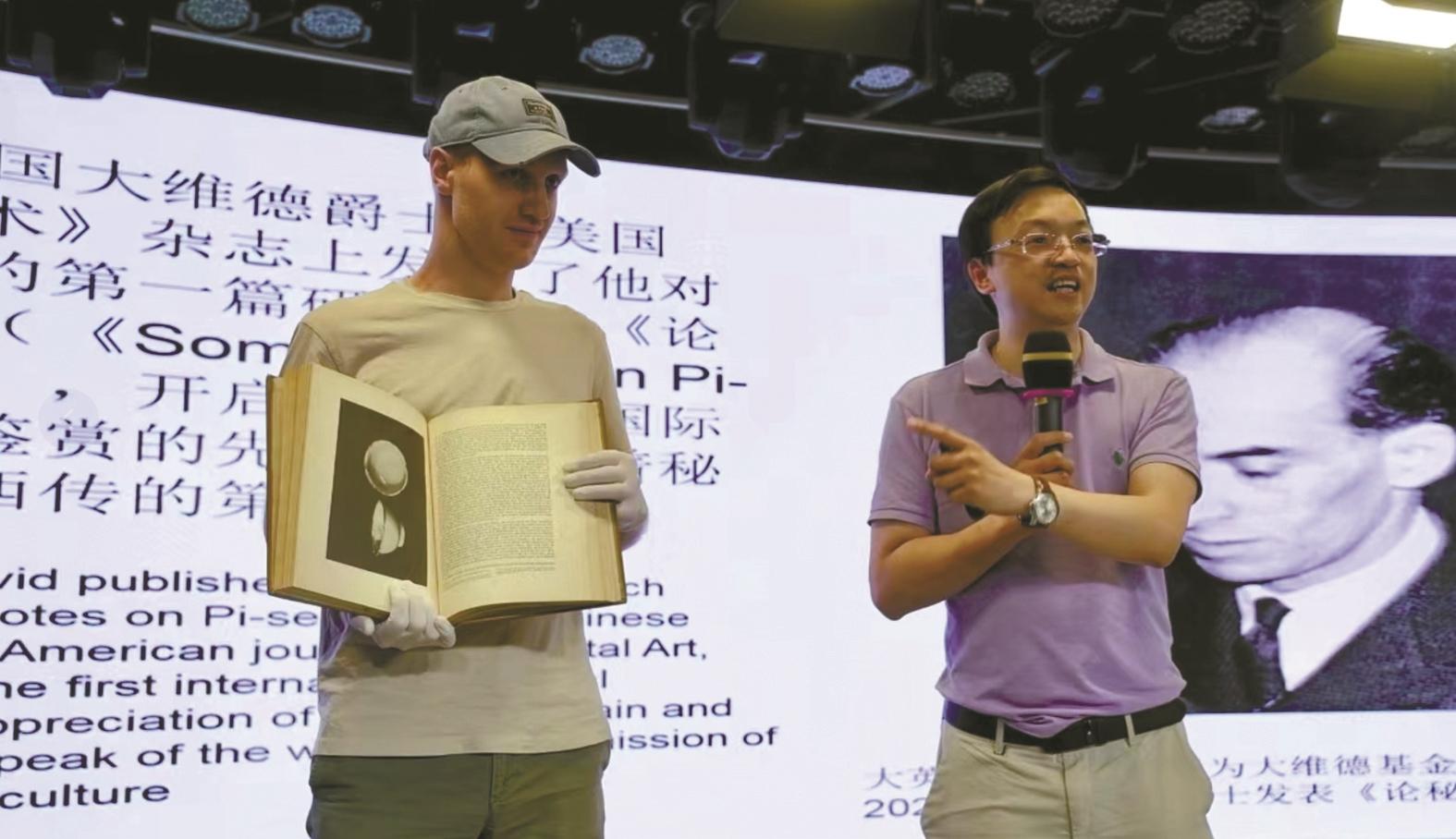

At the symposium, Xu Weiming, a volunteer researcher dedicated to celadon cultural heritage preservation, captivated international guests with rare images of the Shanglin Lake Yue Kiln sites and early 20th-century overseas documents on Mi-se Porcelain, discovered earlier this year.

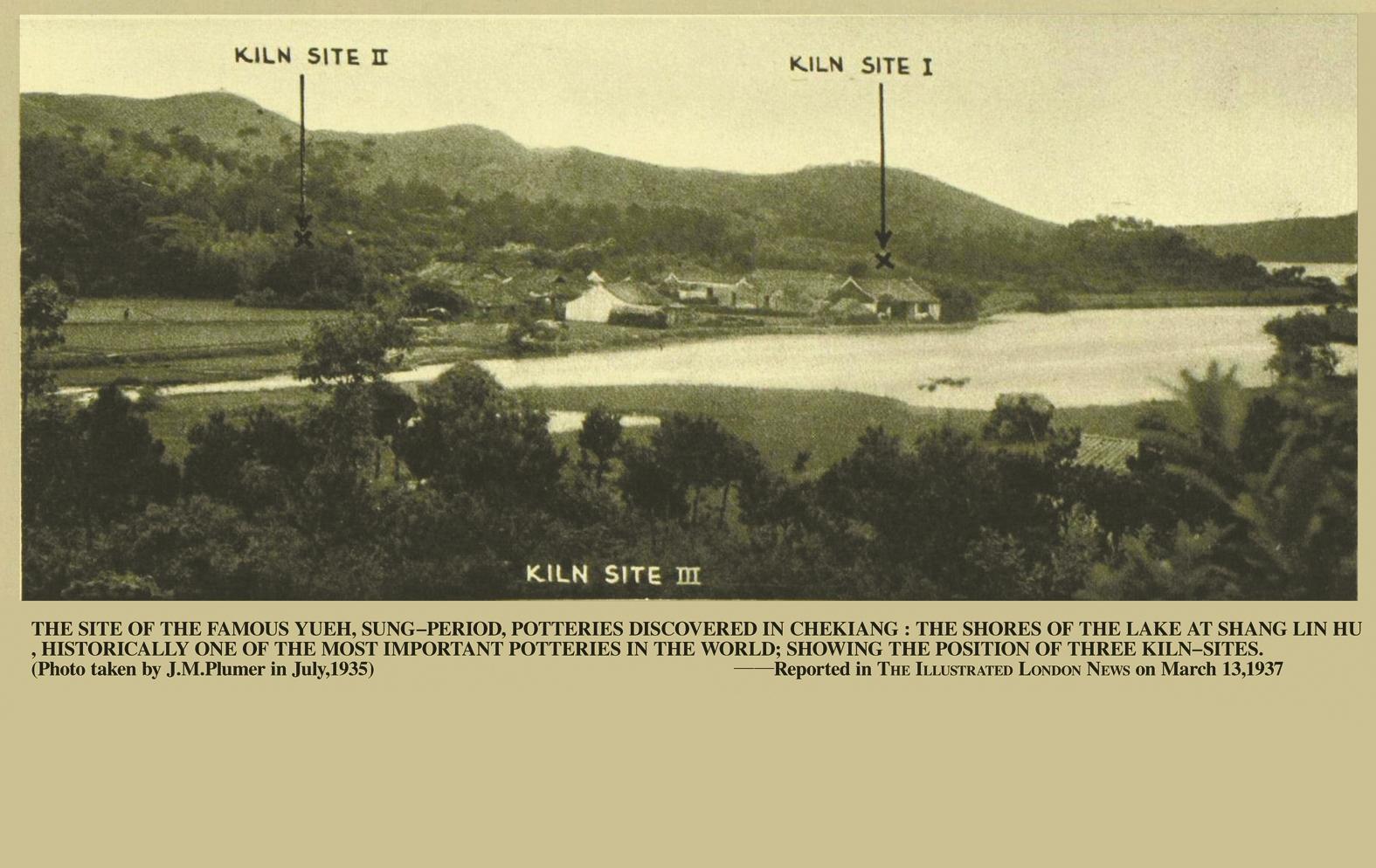

This captivating tale began with James Marshall Plumer, an American who traveled from Shanghai to Hangzhou in July 1935 to visit Shanglin Lake in Cixi. There, he photographed the Yue Kiln sites. A year and a half later, he published these photos and three articles in international journals, formally introducing Shanglin Lake and the Yue Kilns’ Mi-se Porcelain to the rest of the world. According to Li Zuhao, former director of the Cultural Relics Protection Center of Cixi and a senior research expert on Yue Kiln celadon, Plumer was the first Western scholar to study the Yue Kiln archeological sites at Shanglin Lake.

As a poem by Tsangyang Gyatso says, “Whether you see me or not, I am here.” These photos and articles have always been present in historical publications. While some foreign ceramics researchers might have seen them, it seemed that no Chinese researcher had found them until earlier this year, when Xu discovered them while reviewing English-language literature.

1

Researcher Awed by

“Mi-se Porcelain hut”

Who was James Marshall Plumer?

Plumer, a Harvard graduate of 1921, joined the Customs Service in China in 1923. He worked in several cities, including Shanghai.

High wages and long vacations made the Chinese Customs Service an attractive employment option for graduates of prestigious Western universities. In 1874 alone, the Customs Service recruited four graduates from Harvard.

James and his wife Carol shared a hobby of visiting ancient kiln sites to collect porcelain shards.

On May 15, 1935, Chen Wanli, honored as the “father of Chinese ceramic archaeology”, arrived at Shanglin Lake for the first time, becoming the first Chinese scholar to investigate the Yue Kilns site. Coincidentally, Plumer traveled to the same area in July of the same year.

Why did Plumer decide to go to Shanglin Lake? He gives a detailed account in the first of three articles he published on the Mi-se Porcelain of Shanglin Lake.

In the spring of 1935, a Chinese friend gave Plumer three pieces of gray-green glazed porcelain that closely resembled each other, claiming they were from an unknown kiln site. After research, Plumer discovered that these pieces originated from an area near Hangzhou. Determined to pinpoint the exact location, Plumer traveled from Shanghai to Hangzhou and managed to find out about Shanglin Lake. With assistance from Robert Ferris Fitch, president of Hangchow Christian College, and a missionary in Yuyao, Plumer arrived at the south bank of Shanglin Lake in early July 1935.

Plumer wrote, “As yet, the outer world knows little of the site at Shang Lin Hu, where the famous Yueh ware was made.” Evidently, few of his contemporaries were aware that Shanglin Lake was the home of the Yue Kilns’ Mi-se Porcelain.

What did Plumer see at Shanglin Lake? The photos he published can reveal the story.

In one photo, Plumer placed his hat as a reference in the middle of a broken porcelain sagger. The shards within the sagger appeared to be mostly one-third the size of the hat.

In another photo, villagers near the Shanglin Lake Yue Kiln Site stroll about, with an entire wall of a house behind them constructed from porcelain fragments. Plumer dubbed such a structure a “Mi-se Porcelain hut”, noting that such a rare sight could only be found in Germany’s Meissen and France’s Sèvres.

On his trip, Plumer discovered three ancient kilns, which he marked on a map in his published article. Using Plumer’s route and landscape feature comparisons, Xu and other Yue Kiln researchers in Cixi confirmed that one of them is the Hehuaxin kiln, which still exists. The other two, however, have since been covered by new villages and roads.

2

Three Articles Bring

Global Attention

In late 1935, Plumer was appointed Lecturer on Far Eastern Art at the University of Michigan and returned to the US.

For reasons unknown, it was not until March 1937 that Plumer published his first report on his investigation of the Yue Kiln sites at Shanglin Lake.

One of the earliest appeared in the March 13, 1937 issue of The Illustrated London News, with the title “Long-Lost Chekiang Kiln-Sites, Where Precious Sung Pottery is Dug out for Building Material!” and the subtitle “The Origin of the World-Famous ‘Secret Colour’ Ware Discovered”. This article explains studies Plumer conducted at the Shanglin Lake Yue Kiln Site.

Although historical scenic photos of Shanglin Lake exist, none captured the kiln area. The photographs in Plumer’s article provide a clear view of the sites, offering their first known images from the 1930s.

In the March 20, 1937 issue of The Illustrated London News, Plumer published an article titled “The Source of the Celebrated Sung ‘Secret Colour’ Ware Discovered”, with the subtitle “Precious Yueh Shards, Including the Earliest Pottery Dating Found in China”.

In late 1937, Plumer released yet another article titled “Certain Celadon Potsherds from Samarra Traced to Their Source” in the American publication Ars Islamica. He stated that “...several of the celadon shards from Samarra may not only now be identified with one of the rarest Chinese wares, the ware of Yueh or pi-se-yao, but that they many also be traced to their original place of manufacture on the southern shores of a small lake, the Shang Lin Hu, near Ningpo, Chekiang.” In other words, Plumer believed that certain porcelain shards found in Iraq came from Shanglin Lake. Plumer’s view was later confirmed by contemporary archaeologists.

It can be inferred that during the Tang and Song dynasties, Yue Kiln celadon was produced at Shanglin Lake and its surrounding regions, then shipped from the port of Mingzhou to various parts of Asia. It was for this reason that Plumer attached high cultural value to the Yue Kiln sites at Shanglin Lake. “It is well-nigh impossible to over-emphasize the significance of this Yueh ware site. Further investigation, including, it is to be hoped, systematic excavation, promises to fill in a tremendous gap in the history of Chinese ceramics.”

While the three articles lay awaiting discovery in the archives, Xu Weiming worked to bring global recognition to the Shanglin Lake Yue Kiln Site.

Xu has had a long-standing passion for Yue Kiln celadon. In 2021, he discovered clues that Plumer had visited Shanglin Lake from pictures shared by a porcelain teacup collector in Beijing, though the details were scant. On Chinese New Year 2024, Xu made a significant breakthrough while looking up information in English-language academic archives. He found Plumer’s earliest article introducing the Yue Kiln site at Shanglin Lake and, for the first time, uncovered Plumer’s photographs from the Hehuaxin Kiln site (named “Kiln-Site I” by Plumer), some of which had never been seen in Chinese publications. These images, taken in July 1935, are of immense historical value.

3

An Invitation to Plumer’s Descendants

Xu points out that some of Plumer’s statements are inaccurate based on today’s archaeological findings. For instance, in the captions of porcelain shard photographs, Plumer described several Tang Dynasty Yue porcelain pieces from the Hehuaxin Kiln site as being from the Song Dynasty. He also mistakenly identified a five-duct ware, a burial offering made in Longquan, Zhejiang, as originating from the Yue Kiln. However, Xu acknowledges that overall, Plumer’s research on the Yue Kilns and Mi-se Porcelain of Shanglin Lake was far ahead of his time.

Plumer brought global attention to the Shanglin Lake Yue Kiln Site through his three articles published in both the UK and the US, with two translated into Japanese. These publications not only disseminated knowledge about the Shanglin Lake Yue Kiln Site and its Mi-se Porcelain but also attracted international ceramic researchers to Shanglin Lake, garnering widespread recognition for this cultural heritage.

Interestingly, Xu also stumbled upon a little-known chapter of Plumer’s past.

Due to Plumer’s extensive knowledge of China, during World War II, he collaborated with Liang Sicheng, the renowned Chinese architecture historian, and other Chinese and American scholars to complete the “Map and List of Chinese Heritage Sites”. This map was presented to Major General Claire Lee Chennault’s 14th U.S. Army Air Force Command, aiding in the protection of cultural relics and heritage sites from air raids in the China war zone. For this invaluable contribution, he earned the title “Defender of Heritage”.

After Plumer’s death on June 15, 1960, the Yue Kilns porcelain shards he collected from Shanglin Lake remained in the collections of the Museum of Art, the Museum of Anthropological Archaeology, and the Kelsey Museum of Archaeology on the Ann Arbor campus of the University of Michigan, as well as the Harvard University Art Museum.

“I hope that these museums at the University of Michigan could consider forming a partnership with Cixi’s Yue Kiln Celadon Museum to jointly advance the research of Yue Kiln Mi-se Porcelain. Additionally, I hope to find the descendants of Plumer and invite them to visit Shanglin Lake, so that the Plumer family and Shanglin Lake could continue our friendship.”

In Xu’s view, even the most exquisite Yue Kiln celadon is just an object; it is the people behind these artifacts that imbue them with warmth and vibrancy. As the 90th anniversary of Plumer’s visit to the Yue Kiln site at Shanglin Lake approaches in 2025, Xu envisions a heartwarming scene: Plumer’s grandchildren or great-grandchildren arriving at Shanglin Lake, listening to him recount the story of their forebear’s visit from 90 years ago.

If you are affiliated with the Museum of Art, the Museum of Anthropological Archaeology, the Kelsey Museum of Archaeology at the University of Michigan, the Harvard University Art Museum, or if you are one of Plumer’s descendants, we invite you to reach out to Mr. Xu Weiming at 1550083758@qq.com.