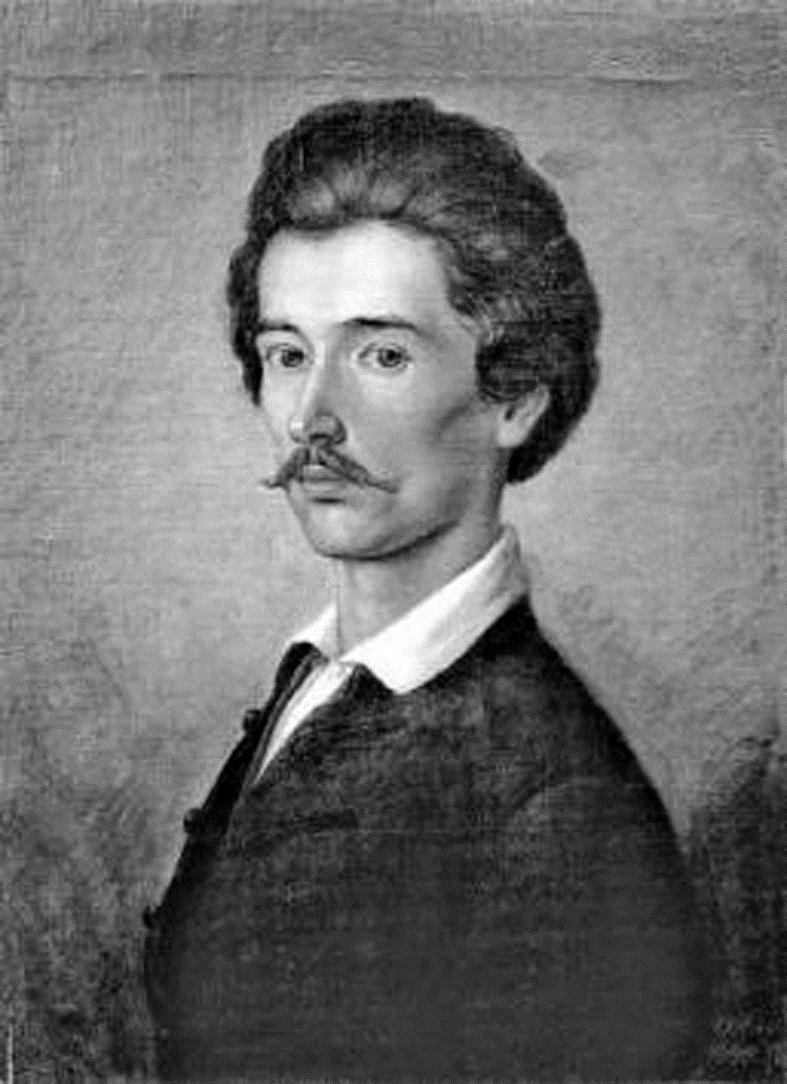

Love, or liberty?

Fate once stranded Petőfi and Yin at the crossroads. Eventually, they both embraced “liberty” over “love”.

Petőfi described love as the wellspring of his poetry. Over a mere three years with his wife, Júlia Szendrey, he crafted over a hundred love poems for her, many immortalized as Hungarian lyrical classics. In his oeuvre, Petőfi conveyed the yearning for a happy and harmonious family life, holding it dear as his interpretation of “living in clover”.

Amidst the whirlwind of revolution sweeping across Europe, including Hungary, Petőfi saw himself torn between romantic bliss and patriotic sorrow. This inner conflict inspired the composition of the epic Szabadság, szerelem.

On Petőfi’s scale of life, love, and liberty, liberty trumped all. And a century later, Yin arrived at the same conclusion. In addition to romantic relationships, Yin also distanced himself from familial ties. His older brother had once served as a paternal figure but stood ideologically opposite, creating a chasm that divided them.

In July 1929, Yin’s participation in strikes among the silk weavers in Shanghai threw him in jail again. This third imprisonment starkly highlighted to him the irreconcilable nature of class conflicts. In his letter “To an Elder Brother”, Yin poured out his heart, acknowledging, “You have been an exceptional elder brother. Before your departure abroad, you sponsored my education at D University and provided solace with words of encouragement. Though our father passed away years ago, your thoughtfulness echoes his. Your gentle demeanor, reminiscent of a soft cloud, soothes pains and nerves.”

Yet, Yin was aware of what he had to disown: “To you, I remain a brother; but to me, you embody an opposing class.” He wrote: “The breach between our social strata widened beyond reconciliation. With the surge of antagonism between the two classes, our brotherhood is doomed to perish.”

The agony visualized in Yin’s words can never be more palpable: “Farewell,/ brother,/ farewell.// You go your own way,/ and I go mine.// Perhaps our next encounter will mark a clash of battle.//”

Ties that bind

Despite the nearly century-long gap between them, Yin and Petőfi are united by the translation of Szabadság, szerelem.

After Yin’s sacrifice, Lu Xun (1881–1936), the famous Chinese writer who was an intimate friend of Yin’s, stumbled upon a German Petőfi volume. Beside one of the poems, he spotted Yin’s inscription of Szabadság, szerelem in Chinese.

Shi Fuming, an authority on Yin Fu’s works from Xiangshan, believes that Yin’s rendition transcends mere translation—it also illustrates his prioritization among life, love, and liberty. Yin consistently chose liberty, much like Petőfi, reflecting their shared experiences and values.

When personal love contradicted national imperatives, they staunchly sided with the greater good. Never faltering, they confronted each challenge head-on, quietly enduring the heartache of estrangement or even permanent separation from loved ones.

In defense of liberty, they didn’t hesitate to terminate relationships with anyone obstructing the nation’s progress, whether a sibling or an old friend. Petőfi exemplified such resolve and during his military service he radically opposed those advocating for compromise with the Habsburg monarchy (13th century - 1918), even if they were his friends. Similarly, when confronted with critical national decisions, Yin severed ties with his brother, despite acknowledging his kin’s kindness. Furthermore, he authored a public letter against the rival class represented by his brother.

President Xi, in his signed article, quoted an old Chinese saying: “No mountain and ocean can distance people with shared aspirations.” This proverb finds resonance in the timeless cross-border friendship between Petőfi and Yin, which has proven to be “more precious than gold”. Their enduring bond also mirrors the shared aspirations and responsibilities between China and Hungary.

May the long-standing China-Hungary friendship continue to mature — as mellow and rich as Tokaji wine.

The poem Szabadság, szerelem (Liberty and Love) in Hungarian and Chinese

Szabadság, szerelem

Szabadság, szerelem!

E kettő kell nekem.

Szerelmemért föláldozom

Az életet,

Szabadságért föláldozom

Szerelmemet.

自由与爱情

生命诚宝贵,

爱情价更高;

若为自由故,

二者皆可抛。